영어 세미나에서 '예외상태'라는 개념에 대해서 발표를 하였습니다. 내용적으로나 문법적으로나 그다지 자신이 없는 부분이 많은데, 코멘트를 해주시면 공부하는 데 큰 힘이 될 것 같습니다!

1. The Exclusion of the Exceptions from Law

If we understand the law as the universal norm that has to be applied in the same way to all phenomena, the law cannot allow exceptions for its cases. The concept of law excludes exceptions from itself. Technically, the law with room for exceptions is a kind of oxymoron. It is contradictory to regard an order as the universal norm but to give immunity to some cases from the norm. Kant clearly points out the law’s exclusion of exceptions in his moral philosophy. He argues that to make exceptions in a law collapses the universal norm into a contradictory self-justification: “[I]f we weighed all cases [of the transgression of a duty] from one and the same point of view, namely that of reason, we would find a contradiction in our own will, namely that a certain principle be objectively necessary as a universal law and yet subjectively not hold universally but allow exceptions.” (Kant, 1997: 34)

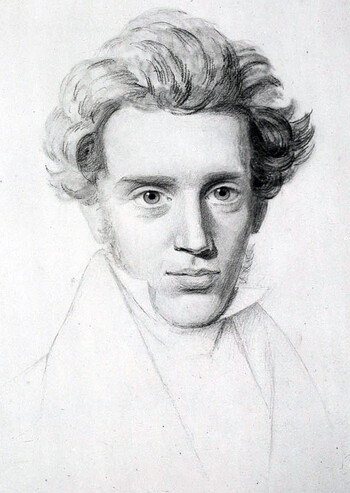

Immanuel Kant and Søren Kierkegaard

2. The Deconstruction of Law from an Exception

However, if the law is established by excluding exceptions, it means that an exception has the power to deconstruct the law. All you have to do in order to criticize the law is to find out an exception to it. After the exception appears, the law cannot be the universal norm anymore. At least, it has to revise the domain of application by restricting its original provision. Here is the reason that Kierkegaard emphasizes the significance of the exception. According to him, the exception is the evidence of the possibility that sometimes “the single individual” (such as Abraham in Genesis 22:1-19) can overcome the universal norm. “[T]he single individual as the single individual is higher than the universal, is justified before it, not as inferior to it but as superior.” (Kierkegaard, 1983: 55-56) That is, the single individual as an exception is sufficient to show the limit of the law. Even one single exception abolishes the universality.

3. The Exception Excluded from Law or Controlled under Law

Schmitt is the first philosopher of law who introduces Kierkegaard’s emphasis on the exception into jurisprudence. He summarizes his main idea with terse prose: “Sovereign is he who decides on the exception. […] The decision on the exception is a decision in the true sense of the word. Because a general norm, as represented by an ordinary legal prescription, can never encompass a total exception, the decision that a real exception exists cannot therefore be entirely derived from this norm.” (Schmitt, 1985: 5-6) The juristic position that Schmitt criticizes is Kelsen’s legal positivism. Against Kelsen’s positivism claiming that legal judgments can be mechanically derived from legal prescriptions, Schmitt’s decisionism argues that norms constructed in ordinary states cannot cope with the exception. In order to control the exception, (i.e., in order to establish the law) norms have to depend on the sovereign who has the authority to decide whether a case is the exception or not. That is, (a) if the sovereign decides to ignore the case, it cannot be the exception to the law. Nothing can threaten the universality of legal prescriptions anymore. However, (b) even if the sovereign decides to take the case as the exception, it still cannot defeat the law. The sovereign can proclaim a new law to deal with the exception. No matter what the sovereign decides, the exception loses their deconstructive power. It is excluded from the established law or controlled under the new law.

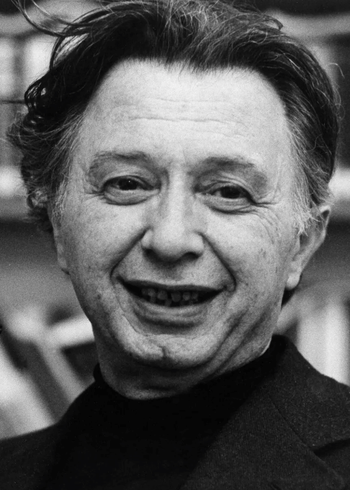

Carl Schmitt and Jacob Taubes

4. From Jurisprudence to Natural Science

Interestingly, Schmitt’s idea can be extended to the general problem of the universality of laws. Taubes claims that the concept of exception does not need to be confined to jurisprudence. Rather, it can be significant even in natural science: “The question is whether you think the exception is possible—and it is on the exception, after all, that the whole law of natural science runs aground, because natural science is based on prognosis. (I’m not the authority on this, nor am I so stupid as not to notice the metaphysical premises of this thinking.)” (Taubes, 2004: 85) That is, all kinds of laws (not only juridical laws but also scientific laws) are established by excluding or controlling the exception. Whether you believe that the exception is possible determines whether you acknowledge that the law is universal. Therefore, the logic of the exception is a covered foundation of law, as Schmitt says: “The rule proves nothing; the exception proves everything: It confirms not only the rule but also its existence, which derives only from the exception.” (Schmitt, 1985: 15)

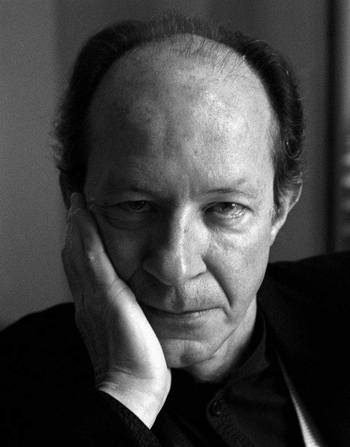

Walter Benjamin and Giorgio Agamben

5. The Two Perspectives on the Exception

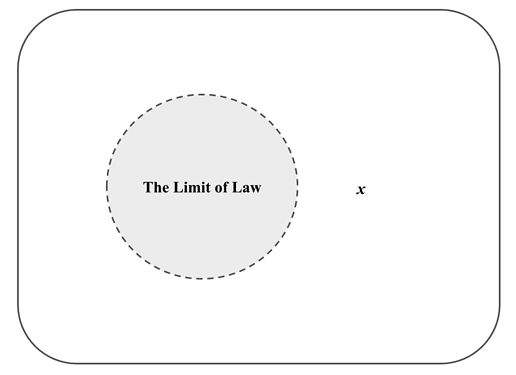

Agamben contrasts Schmitt’s concept of the exception with Benjamin’s one. Though the two people focus on the significance of the exception, they lay emphasis on different aspects. Whereas Schmitt tries to suggest a strategy to exclude or control the exception, Benjamin wants to reveal the deconstructive power of the exception. “The theory of sovereignty that Schmitt develops in his Political Theology can be read as a precise response to Benjamin’s essay. While the strategy of “Critique of Violence” was aimed at ensuring the existence of a pure and anomic violence, Schmitt instead seeks to lead such a violence back to a juridical context.” (Agamben, 2005: 54) See Figure 1.

Figure 1

According to Agamben, the concept of the exception makes “the very limit of the juridical order” (Agamben 2005: 23) an issue. Figure 1 expresses the limit of law with the dashed line since there is no strict limit until the law determines to deal with a case under its juridical order. Therefore, the domain external to the dashed line is the provisional outside of the law. Case x in the domain is regarded as the exception to the law. The difference between Schmitt and Benjamin starts with this situation.

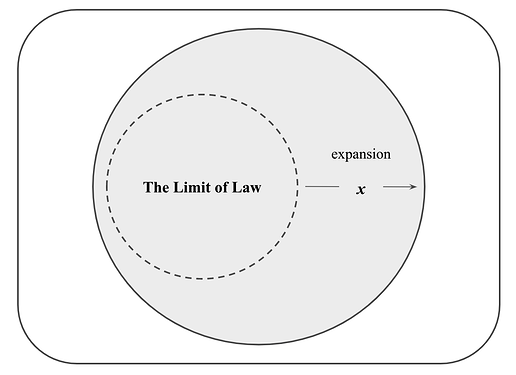

Figure 2

(1) Figure 2 expresses Schmitt’s theory for dealing with the exception. As Agamben explains, “the telos of the theory [Schmitt’s theory] is the inscription of the state of exception within a juridical context.” (Agamben, 2005: 32) Though Schmitt seems to emphasize the significance of the exception, his purpose is to exclude or control the exception. Here is the reason that Schmitt makes the exception dependent on the sovereign’s decision. What is actually important in Schmitt’s theory is not the exception but the decision. By determining case x as the mere exception that can be ignored as a trivial error or be controlled under the new law, the sovereign can expand the law each time he confronts the exception. If he decides to ignore it, he can expand the domain since the outside of the law is disappeared. If he decides to take it as the exception, he can also expand it since the new law to control the exception is constructed from the inside of the law.

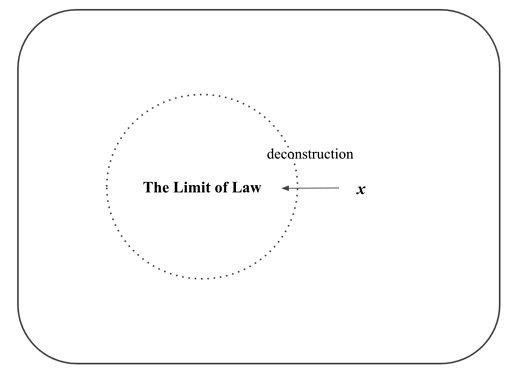

Figure 3

(2) Figure 3 expresses Benjamin’s perspective on the exception. What he wants to show is that there is the “real state of exception (wirkliche Ausnahmezustand)” (Benjamin, 2007: 257) that the sovereign cannot reduce to the law. Benjamin sometimes calls this kind of exception “pure” or “divine” violence in that it is not violence by law. (see Benjamin, 2021: 57-58) “The aim of the [Benjamin’s] essay is to ensure the possibility of a violence (the German term Gewalt also means simply “power”) that lies absolutely “outside” (außerhalb) and “beyond” (jenseits) the law and that, as such, could shatter the dialectic between lawmaking violence and lawpreserving violence (rechtsetzende und rechtserhaltende Gewalt).” (Agamben, 2005: 53) That is, there is no strict law that can cover all cases. It is impossible to expect what exception will threaten the law in advance. The law is abolished each time the exception appears. Of course, as Schmitt argues, we cannot claim that all exceptions have deconstructive power in themselves. However, according to Benjamin, some might be called “real” exceptions. These real exceptions are the possibility of change and revolution from the established law. They are the ground of hope for alternative order, norm, or rule different from the status quo. For this reason, we might poetically say with Benjamin’s expression that the very concept of the exception is the “strait gate through which the Messiah might enter.” (Benjamin, 2007: 264)

References

Agamben, G., State of Exception, K. Attell (trans.), Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Benjamin, W., “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” Illustrations, H. Zohn (trans.), New York: Schoken Books, 2007, 253-264.

Benjamin, W., “Toward the Critique of Violence,” Toward the Critique of Violence, P. Fenves and J. Ng (eds.), Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2021, 39-61.

Kant, I., Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, M. Gregor (trans.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Kierkegaard, S., Fear and Trembling/Repetition, H. V. Hong and E. H. Hong (eds. and trans.), Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1983.

Schmitt, C., “Definition of Sovereignty,” Political Theology, G. Schwab (trans.), Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1985, 5-15.

Taubes, J., The Political Theology of Paul, A. Assmann and J. Assmann (ed.), D. Hollander (trans.), Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2004.