잘 하지도 못하는 영어로 글을 써서 내용이 제대로 이해가 될 수 있을지는 모르겠지만, 여하튼 하이데거의 진리 개념에 대해 발표한 자료를 업로드합니다. 항상 많은 영감을 주시는 Raccoon님께 감사드립니다. 박사 과정에서 진리 이론으로 논문을 써보고 싶은데, 오늘 조언해주신 내용들이 앞으로 제가 공부하는 데 정말 많은 도움이 될 것이라고 생각해요.

Heidegger describes the concept of truth with the terms “disclosedness (Erschlossenheit)” and “uncoveredness (Entdekung).” By introducing these terms in order to deal with truth, he tries to overcome the traditional theory of truth. In this presentation, I will summarize Heidegger’s concept of truth roughly (Ⅰ), explain three discussions around the concept (Ⅱ), and argue my own opinion about how the Heideggerian theory of truth should be refined (Ⅲ).

Ⅰ. Heidegger’s concept of truth

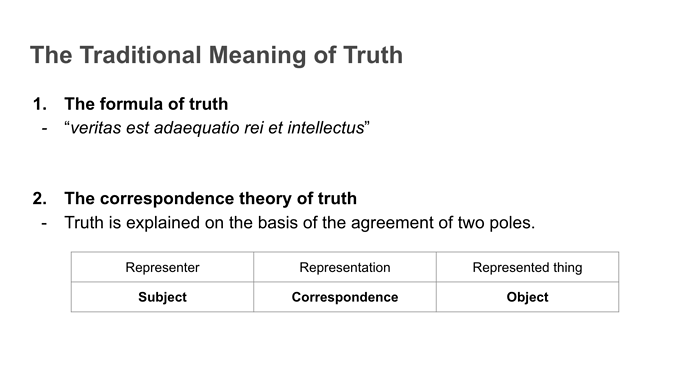

In the history of western philosophy, truth has been defined as the correspondence between judgment and fact for a long time. From Aquinas to early Wittgenstein, a lot of philosophers uncritically accepted the well-known formula of truth, veritas est adaequatio rei et intellectus. It is no exaggeration to say that all traditional discussions of truth were a kind of the correspondence theory of truth. They explained truth with the agreement of two poles: subject (representer) and object (represented thing) That is, a judgment in our subjective mind is true when it corresponds with (represents) the fact in the objective world.

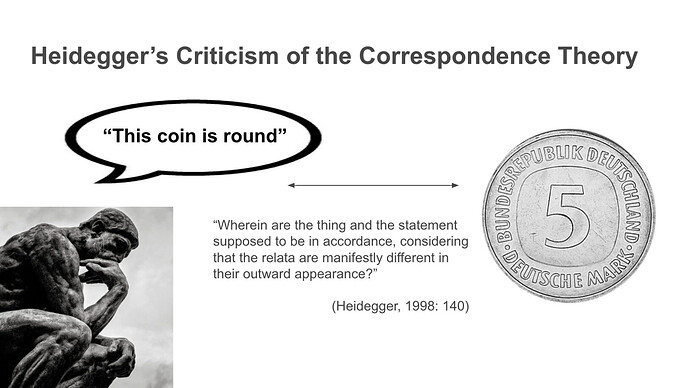

However, Heidegger criticizes that the correspondence theory of truth presupposes the agreement between subject and object as if it could be accomplished without any background practice. He uses an example of coin in order to point out why it is groundless to consider the agreement (or correspondence) as a fundamental relation that do not need further explanations.

[F]or example, we state regarding one of the five-mark coins: this coin is round. Here the statement is in accordance with the thing. Now the relation obtains, not between thing and thing, but rather between a statement and a thing. But wherein are the thing and the statement supposed to be in accordance, considering that the relata are manifestly different in their outward appearance? The coin is made of metal. The statement is not material at all. The coin is round. The statement has nothing at all spatial about it. With the coin something can be purchased. The statement about it is never a means of payment. (Heidegger, 1998: 140)

As Heidegger properly points out, the correspondence between a five-mark coin and “This coin is round” cannot be taken for granted in itself. Whereas the five-mark coin is a metal, the statement “This coin is round” is a sound. There is no natural relation between the two poles. It is an artificial activity to find out the relation under the name of “correspondence.” The traditional theory of truth has failed to question the ground of the correspondence and assumed as if we could discover the correspondence as a natural relation.

For these reasons, against the correspondence theory of truth, Heidegger argues that Dasein’s activity is a “locus” of truth. By using the terms “disclosedness” and “uncoveredness,” he tries to suggest the new concept of truth.

Uncovering is a way of Being for Being-in-the-world. Circumspective concern, or even that concern in which we tarry and look at something, Uncovers entities within-the-world. These entities become that which has been uncovered. They are ‘true’ in a second sense. What is primarily ‘true’—that is, uncovering—is Dasein. “Truth” in the second sense does not mean Being-uncovering (uncovering), but Being-uncovered (uncoveredness). [……] hence only with Dasein’s disclosedness is the most primordial phenomenon of truth attained. What we have pointed out earlier with regard to the existential Constitution of the “there” and in relation to the everyday Being of the “there,” pertains to the most primordial phenomenon of truth, nothing less. In so far as Dasein is its disclosedness essentially, and discloses and uncovers as something disclosed to this extent it is essentially ‘true.’ Dasein is ‘in the truth. ’ (Heidegger, 1962: 263)

The term “uncoveredness” is introduced in order to emphasize that Dasein’s activity connects judgment and fact. Notice that Heidegger does not intend to claim that there is the natural relation of the two poles, which is ready to be discovered as it is in itself. Rather, what he argues is that the correspondence is accomplished when Dasein finds out something from entities and refers to it with her language. The connection between judgment and fact is arbitrary in that it depends on Dasein’s activity that uncovers the object with the judgment. To be more exact, after a state of affair p is uncovered by Dasein with a sentence “p, ” we can say that ““p ” corresponds to p.” It is when we find out Dasein’s activity as the background practice of the correspondence that the classical definition of truth, ““p ” is true if and only if p.” can have its existential ground.

Furthermore, what entities are uncovered by Dasein depends on how Dasein understands the world. In order to describe the condition of uncoveredness, Heidegger introduces the term “disclosedness.” He points out that Dasein’s understanding of the world is a framework in which what is and what is not are determined. For example, if we accept the Aristotelian understanding of the world, all entities in the world should be reduced to four elements (earth, water, air, fire) and the change of nature should be explained according to four causes (material cause, formal cause, final cause, efficient cause). However, if we agree with the Newtonian understanding of the world, all phenomena that occur in the world should be explained on the basis of physical laws that can be expressed as mathematical formulas. That is, the way that the world is disclosed to Dasein determines the way that entities in the world are uncovered to Dasein. Dasein can find out something as true, only if she is in her understanding of the world.1 Therefore, the disclosedness of the world is the ontological ground of truth. The essential meaning of truth consists in the ontological ground of truth (Truth), which makes possible all kind of discovering of entities (truth). This is why Heidegger argues that “Dasein is ‘in the truth. ’”

Ⅱ. Three discussions around Heidegger’s concept of truth

Although a lot of scholars agree that Heidegger’s concept of truth implies revolutionary ideas, there are several discussions around how to interpret its exact meaning. It seems that the discussions are aroused from ambiguity in Heidegger’s explanation of truth. Because Heidegger often uses the term “truth” in two different meanings, scholars discuss the relation of the two truth: so-called, small “t” truth and big “T” truth.

(1) Is Heidegger’s concept of truth not proper to deal with the truth of an assertion?

It is Tugendhat that realizes the ambiguity in Heidegger’s concept of truth for the first time. In his famous article, “Heidegger’s Idea of Truth,” Tugendhat sharply points out that Heidegger attaches the term “truth” to different phenomena. On the one hand, he employs the term “truth” in narrow sense, in order to mean aletheuein [to tell the truth]. In this case, the term “truth” is related to the truth of an assertion (truth). However, on the other hand, he uses the term “truth” in general. sense, in order to mean apophainestai [to show itself from itself]. In this case, the term “truth” is related to disclosure of the world (Truth). By distinguishing the two meaning of truth, Tugendhat criticizes Heidegger that though his concept of truth is proper to emphasize the significance of Truth, it is not proper to deal with the truth of an assertion. Tugendhat argues as follows:

The specific sense of truth is, as it were, submerged in the notion of uncovering as apophansis . And even the specific sense of untruth is, if not simply left out of account, then at least only subsequently taken into consideration, not only in Being and Time but also in “On the Essence of Truth,” so that its antithesis can no longer be essential to the meaning of truth but is instead taken up with it into the truth—which is of course only logical when truth is entitled apophansis . The specific problem of truth is overlooked but not in such a way that it is simply set aside and so still remains open. Rather, inasmuch as Heidegger holds on to the word “truth” but then deforms its meaning and this again in such a way that we still catch a glimpse of its true meaning, it is no longer possible to see what has been overlooked here. (Tugendhat, 1994: 92)

(2) Does Heidegger radically deform the traditional meaning of truth?

Some scholars argue that Heidegger’s concept of Truth is radically different from the traditional meaning of truth. Vattimo is one of the famous philosophers who support this opinion. Because Vattimo rejects to found philosophical hermeneutic (including Heidegger’s ontology) on any metaphysical or transcendental ground, he tries to understand hermeneutic insights about being, truth, experience, knowledge, etc. as a kind of mere interpretations that appear in the history of philosophy since 20th century (See Vattimo, 1997: 1-14; 75-96). Heidegger’s concept of Truth is also regarded as one of the many interpretations of truth, which is parallel with the traditional meaning of truth. That is, by accepting Tugendhat’s criticism that truth as disclosedness (Truth) is different from the truth of an assertion (truth), Vattimo claims that Heidegger does not want to find out the condition for the traditional meaning of truth but to look for the new concept of truth.2 There is no superiority or inferiority between the two understandings of truth. The only difference that distinguishes Heidegger’s concept of Truth from the traditional meaning of truth is that it is the more popular interpretation of truth than the traditional one.

(3) Did Heidegger correct his concept of truth after the criticism from Tugendhat?

There is a debate around whether Heidegger corrected his concept of truth under the influence of Tugendhat’s criticism. Because Heidegger pointed out in his later essay “The End of Philosophy and the Task of Thinking” (1969) that the question of disclosedness and the question of truth should be distinguished, and this essay is written after Tugendhat’s lecture “Heidegger’s Idea of Truth,” (1964) which is delivered at the University of Heidelberg, some scholars suppose that Heidegger considered Tugendhat’s criticism and corrected his concept of truth. With supporting the position that claims Heidegger did not correct his concept of truth, Zabala summarizes this debate as follows:

[I]t is interesting to note how this [Tugendhat’s] criticism received the immediate approval of Habermas and Apel [……], to the point of their considering it at the origin of a “self-correction” done by Heidegger himself. Apel, in the first part of Toward a Transformation of Philosophy , even went as far as to believe that Heidegger actually accepted this correction in this passage of his essay “The End of Philosophy and the Task of Thinking,” included in On Time and Beind (1969). [……] Although a long debate began among Apel, Pöggeler, Gethmann, Schürmann, Habermas, Rochlitz, and many others on whether Tugendhat’s criticism can be considered the origin of a self-correction by Heidegger himself, it is Pöggeler who first correctly observed that this could not be considered a “self-correction” by Heidegger. According to Pöggeler, [……], “Already in his first lectures Heidegger put forward the demand to take into account the practical and religious truth with the theoretical one.” (Zabala, 2008: 29-30)

Ⅲ. Towards the Heideggerian theory of truth

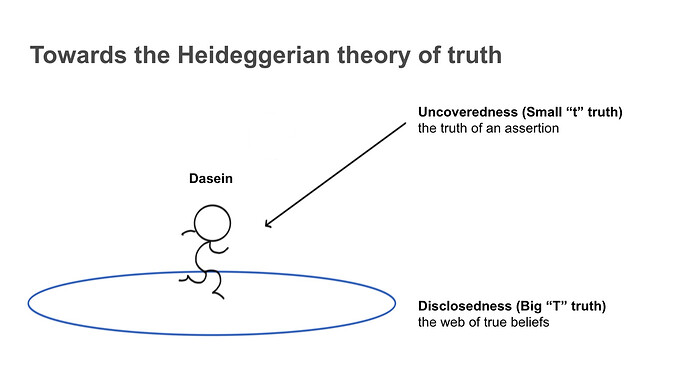

As Tugendhat sharply points out, it is hard to deny that there is ambiguity in Heidegger’s concept of truth. With arguing that the truth of an assertion (truth) should be accomplished on the basis of truth as disclosedness (Truth), Heidegger expands the meaning of truth into the condition of a true assertion. Any traditional theory of truth has never attached the term “truth” to the condition of a true assertion.

However, we cannot conclude from the fact that (a) Heidegger often emphasizes truth as disclosedness that (b) he deals with problems irrelevant to the traditional meaning of truth. Rather, attaching the term “truth” to the condition of truth, it seems that Heidegger considers the web of true beliefs , which we postulated as background knowledge for evaluating our cognition, experience, perception, etc., as the condition of a true assertion . Even if Heidegger himself failed to dissolve ambiguity in his insights into truth, I believe that it is possible to refine the Heideggerian theory of truth by making what the terms “disclosedness” and “uncoveredness” mean explicit.

(1) Big “T” truth: the web of true beliefs

It is the web of true beliefs that can make it possible to evaluate the truth value of an assertion. In our ordinary life, we undertake a lot of beliefs as true without critical assessment. Although some of them turn out to be false later, it is impossible to examine all of the beliefs that we postulated from the first. As Neurath’s boat metaphor rightly describes, we are like sailors who try to fix their boat on the ocean. There is no ground on which we can stand, except the boat we have. Likewise, the web of true beliefs is the condition for assessing what is true or not, which we have to use in order to fix our beliefs. Only if we understand the world on the basis of our web of true beliefs, we can discuss whether an assertion correctly represents the state of affairs. This is why Heidegger attaches the term “truth” to the condition of a true assertion. Truth as disclosedness is not irrelevant to the traditional meaning of truth. Rather, it implies the insight that, by accepting extensive beliefs as true, we acquire the condition for holding a true assertion.

(2) Small “t” truth: the truth of an assertion

The truth of an assertion is accomplished on the basis of the web of true beliefs. Depending on the true beliefs that we accept as background knowledge, we evaluate whether an assertion corresponds to the state of affairs or not. Because the truth value of an assertion is determined in accordance with our background knowledge, it is meaningless to try to find out the correspondence outside of our background knowledge. That is, an assertion is true if and only if it is coherent with other beliefs that we undertake as true. However, an assertion is false if and only if it is incoherent with other beliefs that we undertake as true. Therefore, the criterion for evaluating the truth value of an assertion is coherence. In that the Heideggerian theory of truth emphasizes that whether an assertion is coherent with our background knowledge or not determines the truth value of the assertion, we can categorize it into a kind of the coherence theory of truth.

References

Heidegger, M., Being and Time, J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson (trans.), Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1962.

Heidegger, M., “On the Essence of Truth,” W. McNeil (trans.), Pathmarks, W. McNeil (ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998, 97-135.

Dreyfus, H. L., Being-in-the-World: A Commentary on Heidegger’s Being and Time, Division 1, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1991.

Tugendhat, E., “Heidegger’s Idea of Truth,” Hermeneutics and Truth, B. R. Wachterhauser (ed.), Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1994, 83-97.

Vattimo, G., Beyond Interpretation: The Meaning of Hermeneutics for Philosophy, David Webb (trans.), Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1997.

Zabala, S., The Hermeneutic Nature of Analytic Philosophy: A Study of Ernst Tugendhat, New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

Slide Shows

- Interestingly, Dreyfus compares Heidegger’s concept of disclosedness with Kuhn’s famous concept of paradigm in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. In that Heidegger emphasizes that the truth of a sentence depends on our understanding of the world, his insight of truth is very similar to Kuhn’s analysis of science that the truth of a theory is accomplished within the paradigm of the time (See Dreyfus, 1991: 277-280).

- It is not only Vattimo but also Pöggeler that claims that Heidegger suggests the new concept of truth. Against these two scholars, Apel tries to interpret Heidegger’s concept of truth as an attempt to develop the traditional theory of truth (See Zabala, 2008: 30).

원문: 잡념과 공상 : 네이버 블로그