줄리 E. 메이비의 Picturing Hegel이라는 책을 읽고 있습니다. 헤겔의 『엔치클로페디』의 논리학을 해설한 입문서입니다. 제가 읽어본 헤겔 입문서 중에서 글을 가장 평이하고 깔끔하게 쓰네요. 무엇보다, 그림을 통해 독자의 이해를 돕는 것이 참 좋습니다. 제목도 "picturing Hegel"이고 부제 역시 "an illustrated guide to Hegel's Encyclopaedia Logic"일 정도로 그림에 진심인 책입니다. 『엔치클로페디』의 논리학이 주된 내용이긴 하지만, 1장에서 헤겔의 체계 전체를 철학사적으로 아주 잘 소개하고 있어서, 헤겔에 관심이 있으신 분들이 입문용으로 읽어도 좋을 듯합니다. (그렇지만 단순한 입문서라기엔 600쪽짜리 책이라는 게 다소 함정이지만요.) 메이비는 스탠포드 철학백과의 '변증법' 항목을 작성한 인물이기도 하니, 책의 내용은 두말할 것도 없이 신뢰할 만하다고 봅니다. 책의 서문과 1장에서 흥미로웠던 몇몇 분을 여기도 올려봅니다.

Why study Hegel's logic today? Aside from a historical interest in Hegel's work, there are two main reasons why scholars should still be interested in Hegel's logic. First, the logic offers complex and penetrating definitions of many of Western philosophy's most central and enduring concepts: universality, reason, cause, thing, property, and appearance, just to name a few. […] Second, Hegel's logic is not the standard logic that we teach and learn in schools today. Hegel offered an alternative model of logic that he would have argued is more scientific than the formalistic logics we study now. In the end, we may not come to think that his model is best, but our devotion to our own logic is all the weaker if we fail to engage the challenges posed by his. (p. xiii)

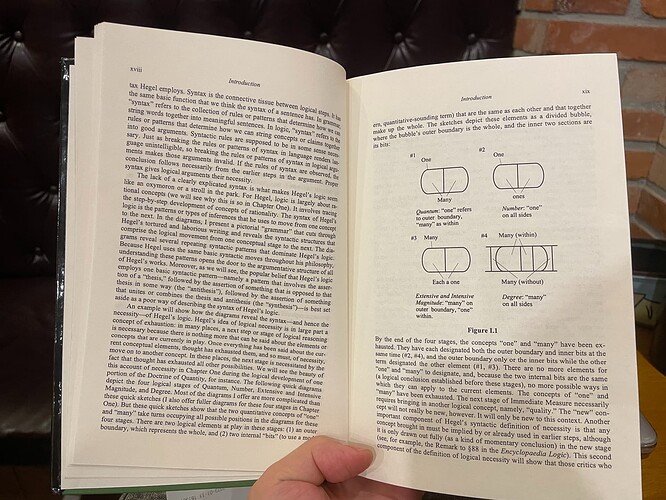

For Hegel, a "logic" that is concerned merely with the form of truth but does not say anything about the contents of truthful forms is inadequate (again, see his Remark to § 162 in the Encyclopaedia Logic). His logic aims to address the contents of truthful judgments and arguments by defining concepts and their relationships with one another in a way that shows how they can be combined into meaningful forms. This aim requires his logic to be much more concerned with semantics—the meanings and meaning-relationships of concepts—than are formalistic logics. (p. xx)

- 헤겔의 논리학이 일종의 의미론의 문제에 관심이 가진다는 주장이 인상적이네요. 헤겔의 논리학을 전공하신 J 선생님도 얼마 전에 비슷한 이야기를 하신 적이 있습니다. 헤겔의 논리학은 사실 의미론이라고요. 전제에서 결론을 도출해내는 형식논리적 타당성 자체보다는, 각각의 개념 사이의 의미 관계를 해명하려는 작업이 논리의 학이라는 거죠.

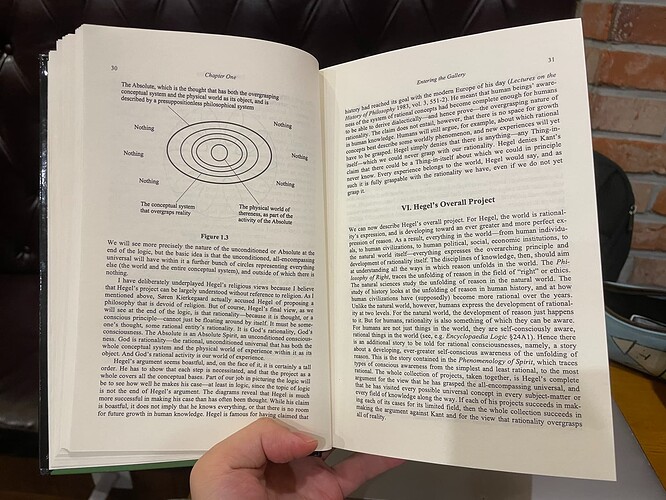

How does Hegel respond to Kant's problem? How does Hegel try to show that we have knowledge not only of our human world of experience, but also of the world itself? This question is especially pressing because Hegel accepted Kant's Copernican revolution to a certain degree. Hegel agrees with Kant that we have knowledge of the world because of what we are like, namely, because of our reason or rationality. So how, for Hegel, can we get out of our heads, so to speak, to the world as it is in itself? The short answer to this question is that, for Hegel, our reason or rationality gives us knowledge of the world in itself because the same rationality or reason that is in us is in the world itself. Kant is wrong to think that reason or rationality is only in us human beings, in our consciousnesses (§§43-44). We can use our reason or rationality to have knowledge of the Thing-in-itself because the world just is, in itself, reason. (p. 6)

- 메이비는 세계 자체 속에 이성과 합리성이 있다는 주장을 칸트에 대한 헤겔의 비판에서 핵심이라고 봅니다. 칸트의 문제는 소위 '사물 자체'를 이성과 합리성 바깥에 알 수 없는 대상으로 상정한 점이기 때문에, 그 문제를 해소하기 위해서는 이성과 합리성 바깥에는 아무것도 없어야 한다는 거죠. 물론, "세계 자체 속에 이성과 합리성이 있다"라는 주장이 정확히 무엇을 의미하는 것인지에 대해서는 논란이 생길 수 있을 것입니다. 형이상학적 헤겔 해석자들은 말 그대로 이 주장이 일종의 '유사 신적 지성'을 도입하는 주장이라고 보고, 비형이상학적 헤겔 해석자들은 이 주장이 (맥도웰의 표현대로) '개념적인 것의 무속박성(unboundedness of the conceptual)'에 대한 주장이라고 보죠. (메이비는 다소 형이상학적으로 해석하는 것 같습니다.)

As we go through the development of Hegel's logic, I will examine from time to time the degree to which I think Hegel's logic supports the traditional claim that Hegel is an idealist. I will suggest that Hegel's logic has some characteristics usually associated with materialism rather than idealism. I will not be the first person, certainly, to read Hegel somewhat materialistically. The 19th century Christian, Danish philosopher, S0ren Kierkegaard (1813-1855), for instance, accused Hegel of being a pantheist (see, for example, Kierkegaard 1992, VI, 122-3). According to pantheism, the world just is God, or, put the other way around, God just is the world. Kierkegaard's charge that Hegel is a pantheist suggests a materialistic reading of Hegel's concept of the Absolute. If the Absolute is God, and if the Absolute expresses itself in the world, as Hegel suggests, then Hegel's God is in the world. Indeed, Hegel's God is in the world so completely, for Kierkegaard, that there is no longer room for a god conceived of as a spiritual entity beyond or independent of the physical world. […] My own view is that, although Kierkegaard's charge is unfair (see Chapter Four, Section VI), Hegel is more of a materialist than is usually believed. (pp. 8-9)

- 헤겔의 입장이 관념론보다는 유물론에 가깝다는 주장도 굉장히 흥미롭습니다. 특별히, 이 주장을 옹호하기 위해 키에르케고어를 끌어들이는 방식도 재미있고요. 확실히, (자주 오해되는 것과 달리) 헤겔은 물리적 세계 너머에 초자연적 공간을 남겨두지 않죠. 메이비가 지적하는 것처럼, 절대자가 신이고, 신이 세계 속에 자신을 표현한다면, 헤겔의 신은 세계 속에 있는 것이 됩니다. 헤겔의 신은 너무나 완벽하게 세계 속에 있어서, 물리적 세계 너머의 혹은 물리적 세계와 독립적인 영적 존재자로 이해되는 신을 위한 공간 따위란 더 이상 존재하지 않는 거죠. 물론, 여기서도 '절대자'나 '신'이라는 용어들을 어떻게 해석해야 하는지에 대한 추가적인 논쟁이 개입하기는 합니다. 저는 헤겔이 '신'을 초자연적 공간에 두려 하지 않았다는 점에 대해서는 동의하지만, 이 주장을 키에르케고어처럼 일종의 범신론으로 해석하거나 메이비처럼 일종의 유물론으로 해석하기보다는, 차라리 지젝처럼 '성령 공동체'에 대한 강조로 해석하는 게 더 적절하다고 봅니다. 성령 공동체(교회)가 세상에서 하는 일들이 곧 신이 세상에서 일으키는 일이라는 식의 해석 말이에요.

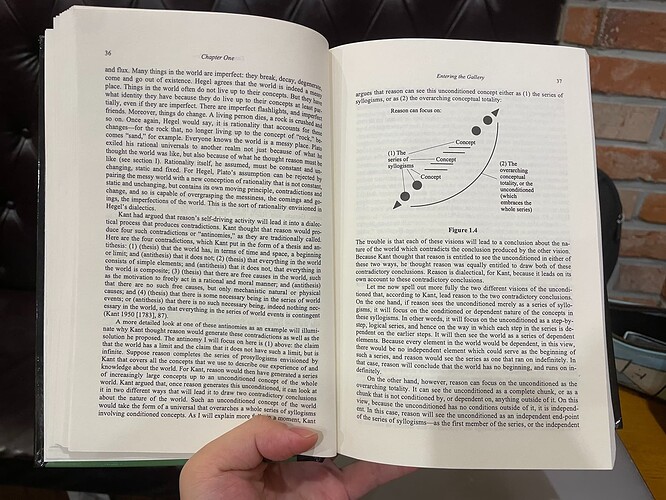

Thus, every one of Hegel's works is an attempt to grasp the unfolding of reason as it occurs in some particular realm of knowledge, be it human history, ethics, natural science, or phenomenology (conscious awareness). Each one tells a dialectical story about self-developing reason in relation to some particular subject-matter. The development of the subject-matter creates and determines, as it goes along, the concepts that are at issue in any particular work. In every case, the same syntactic devices, the same dialectics, are used in the unfolding story that Hegel tells. That is why logic, which outlines the range of syntactic devices for dialectics, underpins all of Hegel's works. (p. 32)

Fichte's synthetic method of logical development can be described with the classical "thesis-antithesis-synthesis" model often ascribed to Hegel. The original judgment is the "thesis," the contradictory judgment would be the "antithesis," and the judgment which resolves the contradiction and introduces the new concept would be the "synthesis." Indeed, Fichte himself used the terms "thetic" judgment-the original assertion, understood as identical to itself and not opposed to anything else (Fichte 1982 [1794], 114)—antithesis, and synthesis to characterize his own model of logical development. Hegel, by contrast, never uses these terms to characterize his method. That Hegel never uses this terminology even though he was certainly familiar with it from both Fichte's and Schelling's work and could have chosen to use it—shows that Hegel did not think that the model applied to his own method of logical development. (p. 39)

- 정반합(thesis-antithesis-synthesis)이 헤겔의 용어나 모델이 아니라는 주장이 여기서도 나오네요.