지난 주에 크리스마스 기념(?)으로 레비나스의 「신-인간?」(『우리 사이』, 김성호 옮김, 그린비, 2019, 90-100)을 읽었습니다. 유대인 철학자인 레비나스가 "하나님이 인간이 되셨다."라는 그리스도교 신학 사상에 담긴 철학적 가치에 대해 논의하는 논문이었어요. 레비나스는 '신-인간'이라는 관념이 '초월성의 애매성'이라는 주제와 '주체성'에 대한 새로운 사유를 담고 있다고 해석하는 것 같더라고요. 그 내용을 영작해 보았는데, 솔직히 의미 전달이 제대로 될 지 자신이 없는 문장들이 많이 포함되어 있긴 하지만, 여기에도 한번 공부한 결과물을 올려봅니다.

Ⅰ. Introduction

Levinas asks in his essay “A Man-God?” to what extent the Christian theological idea that God became a man has philosophical value. Although Levinas does not claim that philosophy can explain all truth in the Christian faith, he believes that it is possible to reveal some value of the idea through phenomenology. In this presentation, I will show how Levinas interprets the idea of the Man-God. I will summarize the phenomenology of Levinas (Ⅱ), explain that the biblical theme of God’s humility implies the notion of transcendence (Ⅲ), and point out that the substitution of the Man-God expresses the unlimited passivity of ourselves (Ⅳ).

Ⅱ. The Phenomenology of Levinas

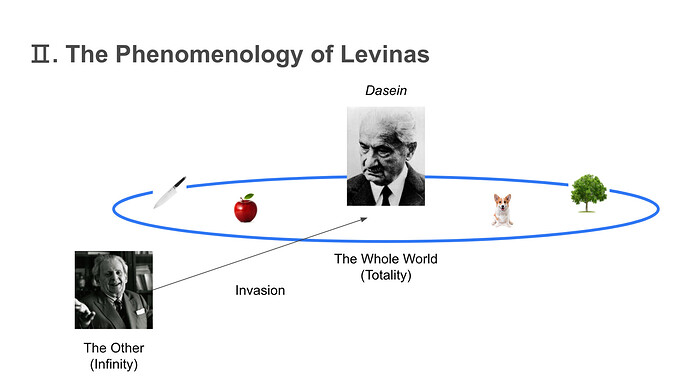

As “Back to things themselves!” is Husserl’s phenomenological motto, it is often said that “Otherwise than being” is Levinas’ one. What Levinas would like to express with his motto is commonly understood by commentators as the criticism of Heideggerian ontology. That is, the word “being” in the motto is used to refer to Heidegger’s phenomenology of being. For Levinas, because the phenomenology of being (ontology) seems to result in totalitarianism, he tries to find out elements (experiences, events, possibilities) in our ordinary life, which cannot be reduced into being. Therefore, “Otherwise than being” means that we need to do phenomenology otherwise than Heideggerian ontology.

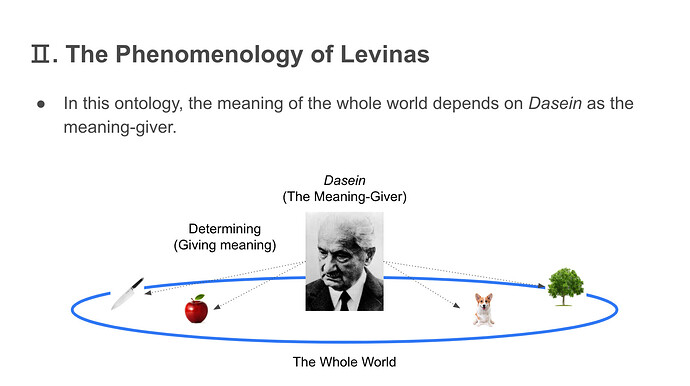

The reason that Heideggerian ontology implies totalitarianism is its ‘Dasein -centric’ character. According to Heidegger, we (as Dasein) are the meaning-givers that constitute the whole structure of the world. What meaning (or significance) an entity has is determined by the relation that the entity has to us. For example, a knife (an entity) can have several meanings to us. It can be a being-for-cutting-foods, if the Dasein is a cook, or be a being-for-threatening-people, if the Dasein is a robber. What an entity is is not different from what meaning the entity has to us. In this ontology, the meaning of the whole world depends on Dasein as the meaning-giver.

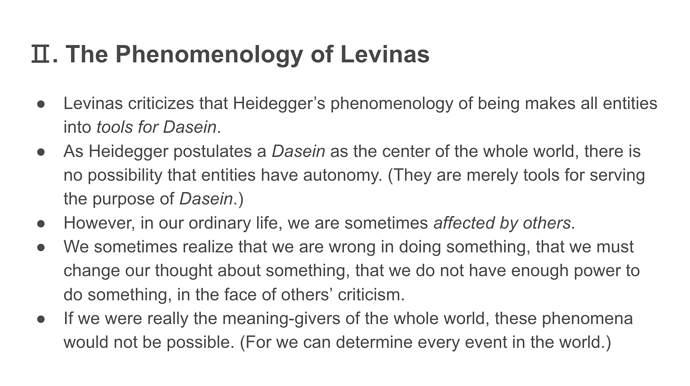

Levinas criticizes that Heidegger’s phenomenology of being makes all entities into tools for Dasein . As Heidegger postulates a Dasein as the center of the whole world, there is no possibility that entities have autonomy. (They are merely tools for serving the purpose of Dasein.) However, in our ordinary life, we are sometimes affected by others. We sometimes realize that we are wrong in doing something, that we must change our thought about something, that we do not have enough power to do something, in the face of others’ criticism. If we were really the meaning-givers of the whole world, these phenomena would not be possible. (For we can determine every event in the world.)

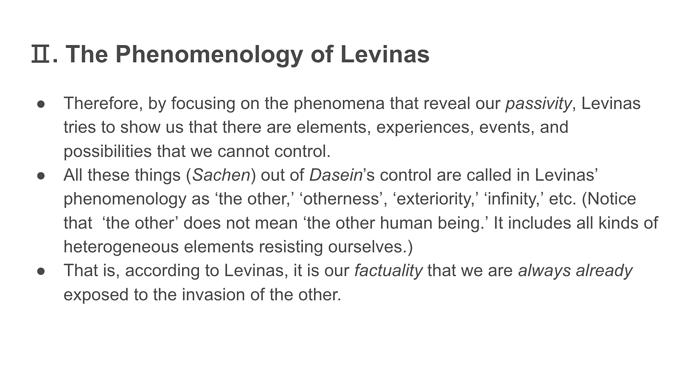

Therefore, by focusing on the phenomena that reveal our passivity, Levinas tries to show us that there are elements, experiences, events, and possibilities that we cannot control. All these things (Sachen) out of Dasein’s control are called in Levinas’ phenomenology as ‘the other,’ ‘otherness’, ‘exteriority,’ ‘infinity,’ etc. (Notice that ‘the other’ does not mean ‘the other human being.’ It includes all kinds of heterogeneous elements resisting ourselves.) That is, according to Levinas, it is our factuality that we are always already exposed to the invasion of the other.

Ⅲ. The Philosophical Interpretation of God’s Humility

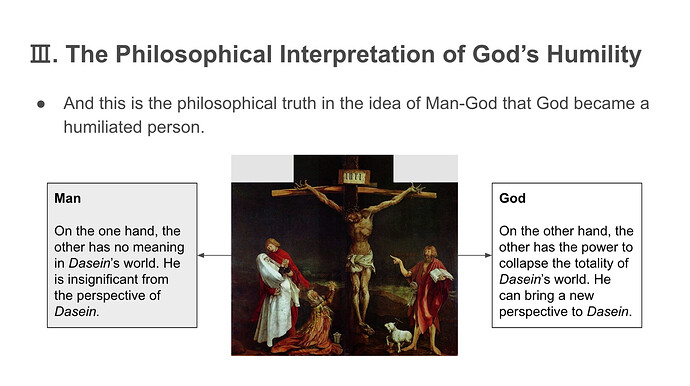

Levinas believes that the idea of the Man-God in Christian theology reflects the phenomena that we experience in the face of the other. He interprets the Man-God as the image of the ‘ambiguity of transcendence’ that the other reveals.

The idea of a truth whose manifestation is not glorious or bursting with light, the idea of a truth that manifests itself in its humility, like the still small voice in the biblical expression—the idea of a persecuted truth—is that not henceforth the only possible modality of transcendence? Not because of the moral quality of humility which I do not wish to challenge in any way, but because of its way of being which is perhaps the source of its moral value. To manifest itself as humble, as allied with the vanquished, the poor, the persecuted—is precisely not to return to the order. […] [T]he humiliated person disturbs absolutely; he is not of the world. Humility and poverty are a bearing within being—an ontological (or meontological) mode—and not a social condition. To present oneself in this poverty of the exile is to interrupt the coherence of the universe. To pierce immanence without thereby taking one's place within it. (Levinas, 1998: 55)

In this paragraph, “the vanquished, the poor, the persecuted” are the images of the other. They are so insignificant to us that we cannot give any meaning to them. However, according to Levinas, the other as “the humiliated person” disturbs Dasein’s world, and “he is not of the world.”

In other words, because they are not in Dasein ’s world, they have the possibility to criticize the whole world that is taken for granted until now. It is this possibility that Levinas focuses on as the ground for transcendence. He points out that even though “the humiliated person” (as the other) seems to be merely weak, he actually has the power to collapse the totality of our old world and to bring a new perspective to us. That is, if we attempt to transcendent our world (to find out salvation from our world), we have to depend on the perspective of the other (whom we regarded as trivial, insignificant and worthless). This is the phenomenon that Levinas calls as ‘ambiguity of transcendence.’ And this is the philosophical truth in the idea of the Man-God that God became a humiliated person.

Ⅳ. The Philosophical Interpretation of Substitution

After discussing God’s humility, Levinas drastically changes the topic (See Levinas, 1998: 58ff). While he has explained the Man-God as an image of the other until now, he interprets it as an image of the subject from now on.

But, in this transubstantiation of the Creator into the creature, the notion of Man-God affirms the idea of substitution. Hasn’t this blow to the principle of identity expressed the secret of subjectivity to some extent? But it is necessary to see precisely to what extent. In a philosophy that, in our time, credits the mind with no other practice than theory, and which leads to the pure mirror of objective structures—the humanity of man reduced to consciousness—does not the idea of substitution allow for a rehabilitation of the subject, which naturalist humanism, quickly losing in naturalism the privileges of the human, does not always achieve? (Levinas, 1998: 58)

Levinas claims that the idea of the Man-God shows the new kind of subjectivity. According to him, the traditional western philosophy has understood subjectivity as activity. Philosophers always have postulated the subject who can determine the meaning of the other. (As we have already seen, the representative example of the subject was Heidegger’s Dasein.) However, the Man-God in the Christian faith, who substitutes for the other, reveals that subjectivity can be defined by ‘unlimited passivity’ or ‘absolute passivity.’ This subject becomes himself by answering to the ask of the other, by accepting the other, and by responding to the command from the other.

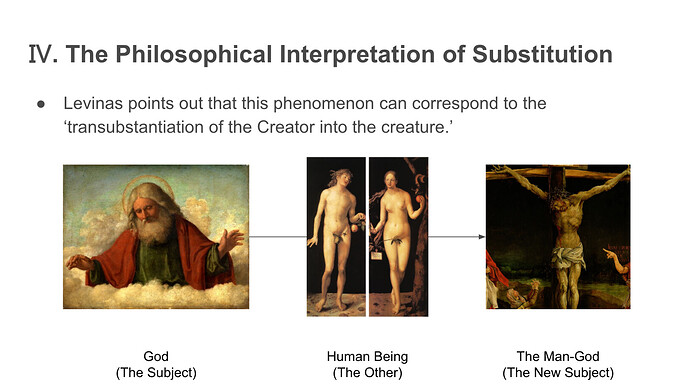

Here, the substitution of the Man-God means the phenomenological event that we become to lose our old perspective and to get the other’s new perspective . It is not a moral activity that we have to do, but a natural process that we always experience in the face of the other. For example, suppose a discussion with the other. Our perspective will be changed if we are faced with serious criticism from the interlocutor. Even if we do not want to change our thought, our web of beliefs cannot remain the same as before in that it already got to know the other’s new perspective. That is, in the natural process of discussion, we passively experiences the changes affected by the other. Levinas points out that this phenomenon can correspond to the ‘transubstantiation of the Creator into the creature.’

Ⅴ . Conclusion

Therefore, Levinas’ philosophical interpretation of the idea of the Man-God has two aspects. On the one hand, Levinas interprets the idea as an image of the ambiguity of transcendence that the other reveals. However, on the other hand, he interprets it as an image of subjectivity that we have. Although the two aspects are different, we do not need to understand them as irrelevant to each other. For what Levinas would like to show with the idea of the Man-God eventually is that the subject transcends his world and becomes himself by experiencing the other.

Reference

Levinas. E., “A Man-God?,” Entre Nous: On Thinking-of-the-Other, M. B. Smith and B. Harshav (trans.), New York: Columbia University Press, 1998, 53-60.

Slides