1. Introduction

P. M. S. Hacker is a well-known scholar whose reading of Wittgenstein’s philosophy is regarded as a standard or orthodoxy interpretation. He often explains Wittgenstein’s criticisms of Platonism or skepticism as a sort of transcendental argument presupposing the bounds of sense. According to Hacker, Wittgenstein’s criticisms have a structure like this: (a) We can see the bounds of sense. (b) The philosophical position in question transgresses the bounds of sense. (c) Therefore, it is nonsensical.

In this essay, I will criticize Hacker’s interpretation of later Wittgenstein. Against Hacker, I will question how it is justified to postulate the bounds of sense. I will also claim that Wittgenstein does not presuppose the bounds of sense in his criticisms of Platonism or skepticism. Then, I will emphasize that what Wittgenstein tries to show us is the bewilderment that we feel in the face of philosophical problems.

2. Hacker’s emphasis on the metaphor of eyes

In order to explain Wittgenstein’s later conception of philosophy, Hacker repeatedly focuses on the metaphor of eyes. He emphasizes that the purpose of Wittgenstein’s philosophy is to give us a surview or synoptic view (Übersicht) on our language. That is, according to Hacker, we sometimes fail to see the structure of language-game. A lot of philosophical problems arise from the lack of eyes to see the condition for using words. What Wittgenstein wants to do is to dissolve the philosophical problems by describing the ‘structure’ or ‘condition’ of our language with the correct view of it. Hacker says as follows:

The most general and recurrent positive formulation of the task of philosophy is the claim that its purpose is to give us an Übersicht , a surview or synoptic view. […] A surview enables us to grasp the structure of our mode of representation, or whichever segment of it is relevant to a given philosophical problem. The concept of surview is central to Wittgenstein’s later philosophy. (Hacker, 1986: 151)

2. Rule: logical syntax or grammar?

According to Hacker, what we should see with the surview is the rule of our language. Wittgenstein often calls this rule “grammar.” Although there are a lot of differences between early and later Wittgenstein, Hacker claims that later Wittgenstein’s “grammar” can correspond to early Wittgenstein’s “logical syntax.” Hacker says as follows:

A surview enables us to grasp the structure of our mode of representation, or whichever segment of it is relevant to a given philosophical problem. The concept of a surview is central to Wittgenstein's later philosophy. It is the heir to the ‘correct logical point of view’ of the Tractatus (TLP , 4. 1 2 1 3), an heir importantly different from the parent. (Hacker, 1986: 151-152)

It is illuminating to juxtapose Wittgenstein’s conception of grammar with his earlier conception of logical syntax. (Hacker, 1986: 179)

That is, as early Wittgenstein tries to see the condition of language by discovering the logical syntax, later Wittgenstein does the same thing by investigating the grammar of our language. Of course, we cannot ignore the differences between the two approaches to our language. (For example, while the former attempts to find out the hidden structure of a language, the latter tries to elucidate the already known structure of a language.) However, the grand strategy is essentially unchanged. The purpose of philosophy is regarded for both early and later Wittgenstein as suggesting the ‘structure’ or ‘condition’ that makes a language sense.

3. Kant and Wittgenstein

In that the grammar of our language draws the bounds of sense , Wittgenstein’s investigation of grammar is similar to Kant’s investigation of the transcendental conditions of our experience. Although Hacker points out differences between Kant’s and Wittgenstein’s philosophy (and his explanation focuses on the differences rather than similarities), he acknowledges that they have “a common grand strategy” (drawing the bounds of sense). Hacker says as follows:

Nevertheless, even though there is little agreement between Kant and Wittgenstein at the strategic level, they shared a common grand strategy. Both sought to show that the Cartesian sceptic traverse the bounds of sense. That distinguishes them importantly from empiricists and rationalist alike. The Kantian tries to show this by arguing that a condition for the sceptic to know what he admits to knowing […] is that he can and typically does know how things, independently of his experiences, are. Wittgenstein took a different route, arguing that the sceptic’s doubts make no sense, that his conception of knowledge of subjective experience is incoherent. (Hacker, 1986: 213-214)

4. How to criticize Platonism or skepticism

Because Hacker’s Wittgenstein can directly see the bounds of sense, it seems that he can judge without hesitation whether the philosophical position in question makes sense or not. In order to judge the philosophical position, Hacker’s Wittgenstein compares it with the cases in which a word or sentence has meaning. For example, let us think about a solipsist (like Descartes) who doubts the external world except for her own consciousness. According to Hacker’s Wittgenstein, this solipsist confuses the grammar of ‘I’ as a subject with the grammar of ‘I’ as an object. That is, it is allowed in our grammar to say that I (as a subject) cannot make mistakes about my feeling, intention, desire, thought, etc. (It is nonsense in our language to say that I do not know what I feel.) However, it is not allowed from the fact that I cannot make mistakes about myself to conclude that I (as an object) necessarily exist. Hacker says as follows:

He [Wittgenstein] distinguished between the use of ‘I’ as object (e.g. I have broken my arm […]) and the use of ‘I’ as subject (e.g. I see so and so […]) The salient feature of the use of ‘I’ as subject is that it is immune to error through misidentification of the subject […] He [solipsist] is of course right that ‘I am in pain’ or ‘I intend to go’ involves no recognition of a person, but he is wrong to jump to the conclusion that the ‘I’ refers to a res cogitans , or indeed to anything else.(Hacker, 1986: 233)

Therefore, Hacker’s Wittgenstein points out that the solipsist is incoherent when she uses the word ‘I’ in her argument. She starts the argument with ‘I’ as a subject but finishes the argument with ‘I’ as an object. In other words, it is a logical leap to claim, from the premise, “I think,” the conclusion, “Therefore I am.” If we can clearly see the grammars of ‘I,’ we can judge the argument as nonsensical. This is the reason why Hacker’s Wittgenstein criticizes that the solipsist transgresses the bounds of sense.

5. How are the bounds of sense justified?

However, it is questionable how Hacker’s Wittgenstein’s premise that we can directly see the bounds of sense is justified. The premise is the core of Hacker’s Wittgenstein’s argument but is too easily taken for granted. It seems that the premise claims what has to be proved. Even Platonists or skeptics often insist that their philosophical theses make sense (namely, their sentences are within the bounds of sense). In fact, philosophers traditionally have emphasized that they have a special ability to see the ‘structure’ or ‘condition’ of reality. For example, think about Plato’s allegory of the cave. In this analogy, a philosopher (unlike other people in the cave) is described as a person who discovers reality under the sun. She can see the structure of reality with undistorted eyes. Plato says as follows:

When one of them [people in the cave] was untied, and compelled suddenly to stand up, turn his head, start walking, and look towards the light, he’d find all these things painful. Because of the glare he’d be unable to see the things whose shadows he used to see before. What do you suppose he’d say if he was told that what he used to see before was of no importance, whereas now his eyesight was better , since he was closer to what is, and looking at things which more truly are? Suppose further that each of the passing objects was pointed out to him, and that he was asked what it was, and compelled to answer. Don’t you think he’d be confused? Wouldn’t he believe the things he saw before to be more true than what was being pointed out to him now? (Plato, 2000: Ⅶ, 515c-d my emphasis)

Hacker’s Wittgenstein does not explain why Platonist’s or skeptic’s ability to see the ‘structure’ or ‘condition’ is an illusion. He merely claims that his surview is right but others’ is wrong, without any argument. It seems that he tries to substitute the Platonist’s (or skeptics’) surview of the ‘structure’ of reality with his surview of the ‘structure’ of language-game. Unless the reason to accept his surview is clear, Hacker’s Wittgenstein’s argument is no more than an attempt to substitute one myth with another myth.

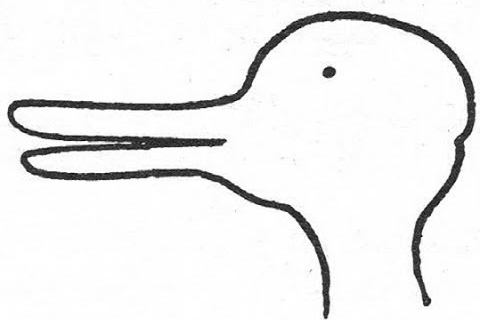

6. Jastrow’s duck-rabbit

Furthermore, Wittgenstein emphasizes that meaning depends on our contexts. As Wittgenstein shows with Jastrow’s duck-rabbit, a picture itself does not have a fixed meaning. Whether the picture represents a duck or rabbit is determined by the perspective of the observer. It can have different meanings to different observers. There is no direct surview that allows us to see what the picture means. If we seriously consider the fact that Wittgenstein himself points out that even the same thing can be seen in different ways, we should be more careful to use the metaphor of eyes in explaining Wittgenstein’s later philosophy.

7. I don’t know my way about.

Therefore, unlike Hacker, I would like to reconstruct Wittgenstein’s argument without depending on the surview of the bounds of sense. Of course, Hacker’s Wittgenstein is correct in that he criticizes that Platonism or skepticism makes no sense (is incoherent). (Cf. Hacker, 1986: 209-210; 214) However, we do not need to employ the surview of the bounds of sense for pointing out the incoherency of Platonism or skepticism. Rather what we need to do is no other than to expose that the philosophical position in question has at least two sentences contradicting each other within itself.

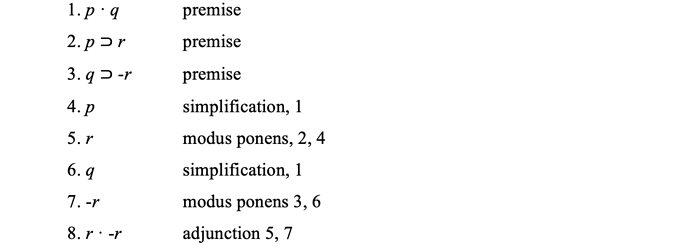

This strategy exposing the contradiction can be expressed by formal logic. For example, if the given philosophical position implies propositions ‘p’ and ‘q,’ and each proposition implies ‘r’ and ‘-r’ (therefore, the following form of argument can be applied to it), then the philosophical position is revealed as nonsensical in that it involves a contradiction:

However, it does not mean that a contradiction automatically makes the philosophical position nonsensical. Rather what makes it nonsensical is the bewilderment that we feel in the face of the contradiction. In fact, for later Wittgenstein, the logical form ‘p · -p’ is not itself necessary or sufficient condition for contradiction. What makes it contradictory is our usage of it. That is, (a) if we can give usage to the logical form ‘p · -p’ in the philosophical position, then there is no problem. In this case, the sentence may have appropriate meaning in appropriate contexts. (b) If we cannot give any usage to the logical form ‘p · -p’ in the philosophical position, then our philosophical position will be jammed up. In this case, the logical form ‘p · -p’ is understood as a symptom that we do not know what to do with the sentence. It reveals that we are jammed up. Wittgenstein says as follows:

I said that a contradiction jams, and this sounds very good. But what the hell does it mean, saying it jams? All that happened was that I said, "Bring me a book and don't bring me a book", and Lewy just stood there; he didn't know what to do. But is this the jamming? [……] When we say it jams, we don't mean simply the fact that people don't react correctly. But we expect a man who knows the language to say, “This makes no sense .” (Wittgenstein, 1976 [1939]: 179 my emphasis)

Therefore, nonsense arises when we fail to find out the way to use contradiction in our language. We do not need to appeal to the bounds of sense in order to criticize the philosophical position in question. In fact, there are no bounds of sense that determine whether a sentence makes sense or not. It is sufficient for us to expose a contradiction in the philosophical position and ask whether it does know what to do with its contradiction. If the philosophical position cannot give any meaning to the contradiction (if it is bewildered by the contradiction), we can judge it as nonsensical. As Wittgenstein points out, “a philosophical problem has the form: “I don’t know my way about.”” (Wittgenstein, 1968 [1953]: §123)

References

Hacker, P. M. S., Insight and Illusion, Revised Edition, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986.

Plato, The Republic, G. R. F. Ferrari (ed.), T. Griffith (trans.), Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Wittgenstein. L., Wittgenstein’s Lecture on the Foundations of Mathematics, C. Diamond (ed.), Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1976 [1939].

Wittgenstein. L., Philosophical Investigations, Third Edition, G. E. Anscombe (trans.), Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1968 [1953].