Ⅳ. Reinterpretation of the “big bold claim”

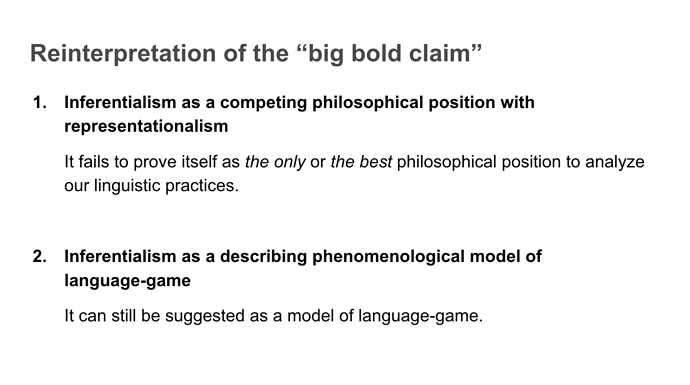

Though it is hard to deny that the three criticisms of inferentialism hit the nail on the head, we do not need to reject all insights in inferentialism. That is, as McDowell points out, inferentialism fails to prove itself as the only or the best philosophical position for analyzing our linguistic practices. However, as Brandom emphasizes, inferentialism can still be suggested as a model of language-game. Therefore, by understanding inferentialism not as a competing philosophical position with representationalism but as a describing phenomenological model of language-game, it seems that the significance of Brandom’s “big bold claim” can be saved from the three criticisms of inferentialism.

1. Therapeutic approach to representationalism

In order to criticize representationalism by constructing alternative theories, the competing philosophical position with representationalism should take the burden to prove its own theories. However, even if the position successfully criticizes representationalism, it is insufficient to accept the alternative theories as superior. Likewise, even if the position successfully constructs the alternative theories, it is also insufficient to criticize representationalism as inferior. To replace representationalism with another philosophical position is to replace a myth with another myth. Insofar as both myths are unjustified, the attempt to replace one with the other falls into the chain of myth.

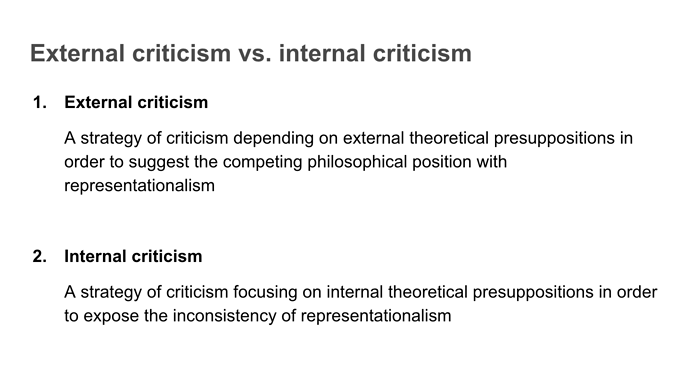

Therefore, the criticism of representationalism should not postulate any other theoretical presuppositions for its position. Rather, it should try to attack representationalism only with theoretical presuppositions representationalism postulates. By criticizing representationalism with its own theoretical presuppositions, we can turn over the responsibility for proving theoretical presuppositions to representationalism without taking any burden itself. That is, the external criticism, which depends on external theoretical presuppositions in order to suggest the competing philosophical position with representationalism, makes as many problems as representationalism does. However, the internal criticism, which only focuses on internal theoretical presuppositions in order to expose the inconsistency of representationalism, deconstructs representationalism without making any problem.

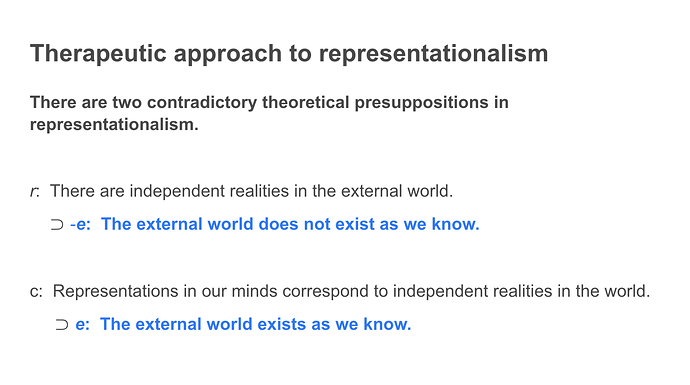

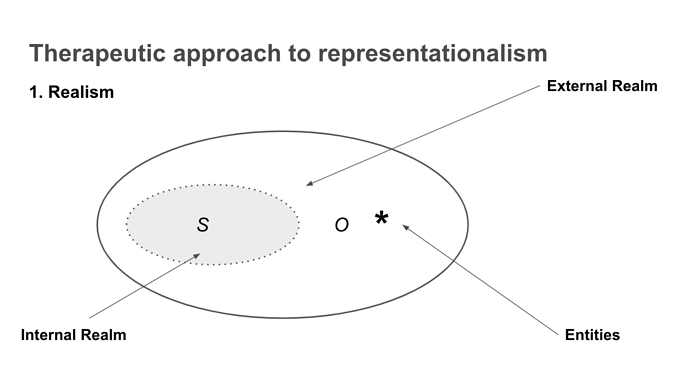

For example, the internal criticism points out that there are two contradictory theoretical presuppositions in representationalism. On the one hand, representationalism postulates independent realities. It claims that entities in front of us are things-in-themselves that resist our will. What the entities really are is not determined by us. Rather, the independent realities exist as the unknown quantity x at the opposite side of us. We can summarize the doctrine of independent realities in representationalism as follows:

r : There are independent realities in the external world.

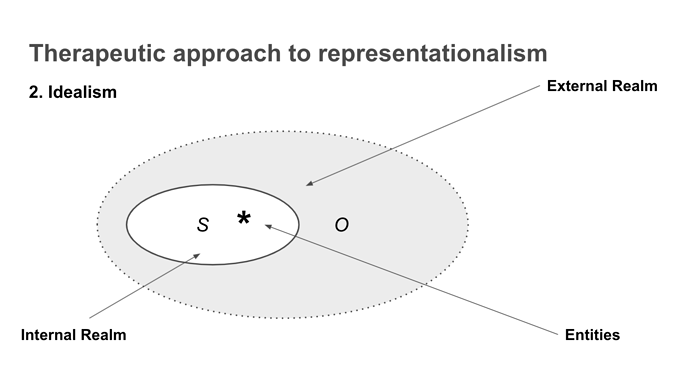

However, on the other hand, representationalism also postulates the possibility of representing independent realities. It claims that our knowledge of entities corresponds to things-in-themselves in any way. What we know about entities is not disconnected from the external world. Rather, representations are causally related to the independent realities with the Given (including sense-data) from them. We can summarize the doctrine of correspondence in representationalism as follows:

c : Representations in our minds correspond to independent realities in the world.

Representationalism is the combination of the two doctrines r and c . Though it postulates entities in front of us as independent realities that we cannot be under our perfect control, it also claims our knowledge of entities as the representation that we can have in our minds. The two doctrines can be combined in the definition of representationalism as follows:

A philosophical position P is representationalism.

= df. A philosophical position P postulates that there are independent realities in the external world and that representations in our minds correspond to them.

The two doctrines of representationalism imply contradictory ideas to each other. They fall into the dilemma regarding how the external world exists. That is, if we acknowledge r, we should claim that the external world is out of our knowledge. How the external world exists has nothing to do with how we understand the external world. The implication of r can be specified as follows:

-e : The external world does not exist as we know.

However, if we acknowledge c , we should claim that the external world is in touch with our knowledge. How the external world exists is not separated from how we understand the external world. The implication of c can be specified as follows:

e : The external world exists as we know.

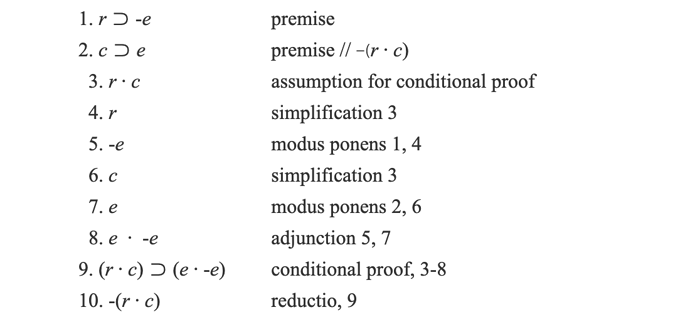

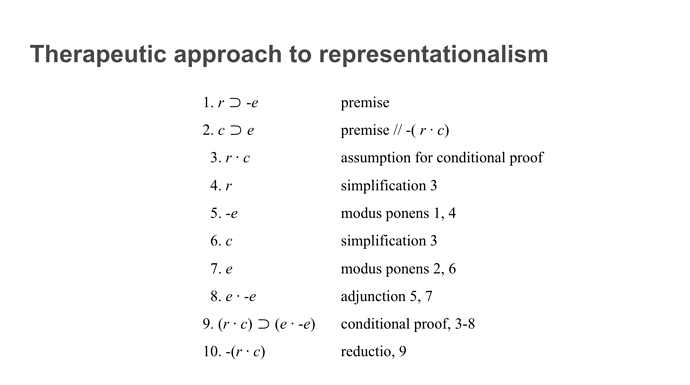

Therefore, the definition of representationalism results in a contradiction. The two doctrines r and c cannot be logically combined. Each doctrine denies the implication of the other. We can argue it in the form of conditional proof as follows:

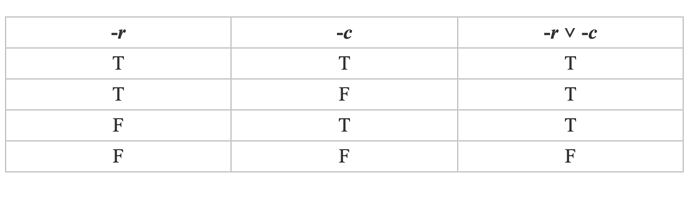

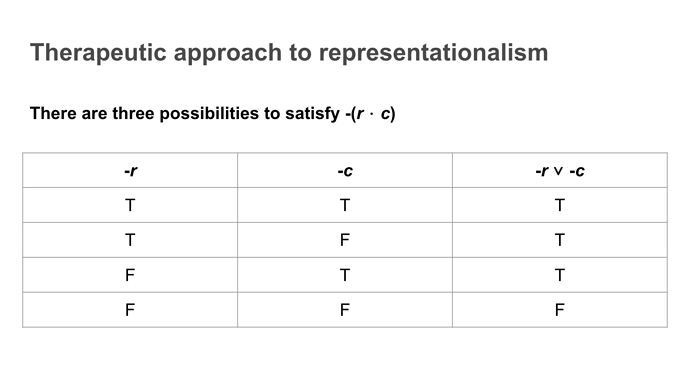

As representationalism is defined with the two doctrines r and c, the negation of representationalism is specified as -(r ⋅ c ). It also can be expressed as -r ∨ -c under the laws of logical equivalence. Therefore, if we acknowledge -(r ⋅ c) as true, we should point out that at least one of the two doctrines is false as follows:

There are three possibilities to satisfy -(r ⋅ c ). First, to deny -r and accept -c. Second, to accept -r and deny -c. Third, to accept both -r and -c.

(1) If we want to deny -r and accept -c , we should support realism against representationalism. In this case, the external world does not exist as we know. The entities in front of us are independent realities that are not determined by us. However, it does not necessarily mean that there are entities absolutely hidden from us (such as Kantian things-in-themselves) in the external world. The claim that there are independent realities that cannot be under our perfect control is different from the claim that there are mysterious realities that can never be known to us. Rather, by giving up the inner realm that should correspond to the external world, realism can justifiably point out that some entities are out of our knowledge without falling into epistemic skepticism.

(2) If we want to accept -r and deny -c , we should support idealism against representationalism. In this case, the external world exists as we know. Our knowledge of entities is not disconnected from the entities themselves. However, it does not necessarily mean that we can grasp the whole external world in our minds. The claim that representations in our minds correspond to independent realities is different from the claim that representations in our minds take God’s eye-view. Rather, by giving up the external realm that should be separated from our mind, idealism can justifiably point out that some knowledge is related to entities without falling into epistemic dogmatism.

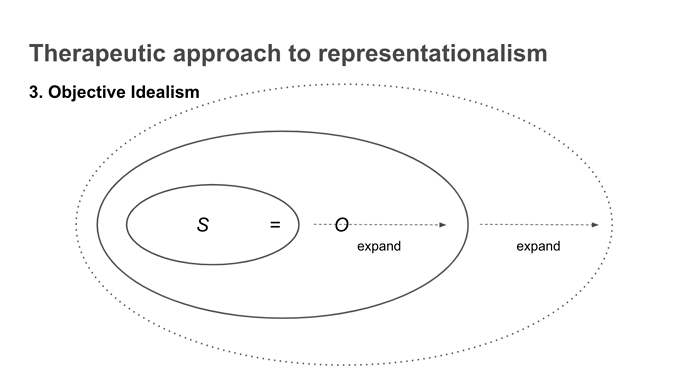

(3) If we want to accept both -r and -c , we can reach the most interesting philosophical position among the three so-called objective idealism (or absolute idealism ). Though it results in a contradiction to accept both r and c as true, it does not result in any contradiction to accept both -r and -c as true. That is, it is possible to claim that some entities are out of our knowledge without falling into epistemic skepticism. Likewise, it is also possible to claim that some knowledge is related to the entities without falling into epistemic dogmatism. The two philosophical positions are compatible insofar as they do not imply the negation of each other. In this case, as the strict distinction between the external realm and the internal realm is disappeared, the difference between realism and idealism is also erased. Therefore, by rejecting the two doctrines of representationalism, objective realism paradoxically restores the true meaning of the doctrines without falling into pseudo-problems. There is no contradiction in the claim that what the entities really are is what we know about the entities and vice versa.

This approach to representationalism can be called therapeutic in that it diagnoses and cures the inconsistency between theoretical presuppositions in order to restore their true meaning. The therapeutic approach does not need any other theoretical presuppositions for the criticism of representationalism. Rather, it helps representationalism to understand what it really means by analyzing the theoretical presuppositions representationalism postulates. Therefore, in fact, there is nothing to be lost in representationalism. What we should do is to understand the theoretical presuppositions in the right way: to understand that there is no contradiction between the claim that some entities are out of our knowledge and the claim that some knowledge is related to the entities.

2. Explicit description of language-game

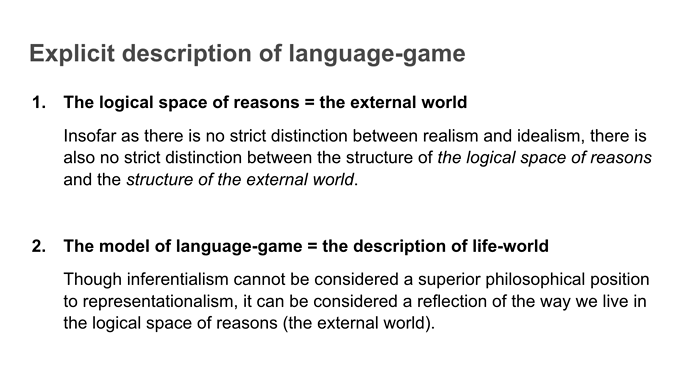

Here, Brandom’s big bold claim comes into its own. Insofar as there is no strict difference between realism and idealism, there is also no strict difference between the structure of the logical space of reasons and the structure of the external world . That is, the model of language-game is in itself as the description of life-world. Though inferentialism cannot be considered a superior philosophical position to representationalism, it can be considered a reflection of the way we live in the logical space of reasons (the external world). Let us suggest some cases that inferentialist theories make explicit.

(1) Experience : Inferentialist theories point out that experiencing something should not be understood as taking the Given from something. The concept of the Given postulates that we can sense an object without any prejudice, any conceptual ability, and any learning process. However, insofar as the structure of the logical space of reasons are the same as the structure of the external world, there is nothing that exists outside the inferential relation between premise and conclusion. That is, even if we believe that we directly sense an object without any filter, we actually infer about it in our epistemic condition, through our perspective, from our background knowledge. For example, in order for something to be perceived as blue, it should be satisfied that we are placed in the normal epistemic condition, our eyes have a reliable differential responsive disposition of the external object, and there is no reason to challenge my perceptual ability, etc. (see Sellars, 1991: 142-148) Therefore, experiencing something should be understood as an implicit process of inference from the premise based on reliable differential responsive dispositions to draw the conclusion about the object in the game of giving and asking for reasons. (see Brandom, 1994: 199-229)

(2) Understanding : Insofar as it is impossible to experience the external world without any filter, it is also impossible to understand the external world in God’s eye-view. The attempt to perfectly represent the whole external world in our minds is merely an illusion that postulates an imaginary perspective outside the logical space of reasons. The external world is nothing different from the logical space of reasons. There is no hidden space that is the external world but not the logical space of reasons. Rather, understanding is a revising process of our web of beliefs. That is, we always already start understanding with our established web of beliefs as default. If the web of beliefs is challenged by a new experience of the external world (or doubt from an interlocutor), we should revise it into a new one. Then, as the new web of beliefs becomes an established one, the previous steps are repeated. (see the default and challenge structure of entitlement in Brandom, 1994: 176-178) Therefore, whenever we perceive a new object, the experience changes our beliefs into a new one. The more we experience, the more we change our beliefs. The process of waving our web of beliefs is endless in that it cannot reach the perfect representation of the external world.

(3) Truth : What is true and what is false are determined by what web of beliefs we have. There is no God’s eye-view to determine whether representations in our mind really correspond to independent entities in the external world. The criteria we depend on in order to judge the truth-value of an assertion are the web of beliefs we always already have. That is, an assertion is true if and only if it is coherent with our web of beliefs. However, an assertion is false if and only if it is incoherent with our web of beliefs. In this inferentialist definition, considering an assertion true is nothing different from undertaking the assertion in our web of beliefs (see Brandom, 1994: 202, 515) Therefore, true assertions of the external world are the same as undertaken assertions in our logical space of reasons. The beliefs that constitute our web of beliefs also constitute our life-world and vice versa. It is one of the reasons that we should deny the “largely true but not translatable” conceptual scheme along with Davidson. Insofar as we acknowledge that truth cannot be separated from undertaking an assertion, it is impossible that an assertion is true but cannot be understood in (translated or interpreted into) our web of beliefs (language). (see Davidson, 1984)

(4) Knowledge : The inferentialist definition of truth is closely related to the inferentialist definition of knowledge. As traditional epistemology defines knowledge with three conditions (belief, justification, and truth), inferentialism also defines knowledge with three practical attitudes that correspond to the conditions (attributing commitments, attributing entitlements, and undertaking commitments). That is, in order for one to be considered having knowledge, (a) we must attribute a commitment to her, (b) attribute an entitlement to the commitment, and (c) undertake the commitment attributed to her as our commitment. (see Brandom, 1994: 201-204, 515) Each condition in the traditional definition of knowledge is interpreted into performances and moves in linguistic practice. Even if one wants to add further conditions (while considering Gettier’s problem), they can be also understood as deontic statuses or deontic attitudes in the game of giving and asking for reasons. (see Brandom, 1994: 675) One of the most significant insights in this inferentialist definition is that knowledge is socially articulated status. It shows us that whether someone can be regarded as having knowledge depends on whether we (as scorekeepers) want to give her a social authority by undertaking an entitled commitment attributed to her. (see Brandom, 1995)

Notice that our reinterpretation of the big bold claim does not understand inferentialism as a competing philosophical position with representationalism. Insofar as the inconsistency of representationalism is diagnosed and cured by the therapeutic approach, there is no reason to build up new theories in order to fill the void of representationalism. Nothing is to be lost. What is needed for us is not to explain semantic vocabulary with new theories but to describe them with undistorted eyes. This is the significance of our reinterpreted inferentialism. It does not remain an ambitious hypothesis for encompassing all kinds of linguistic practices anymore. Rather, it becomes an explicit description of language-game. That is, by making what we are always already doing in the language-game explicit , our reinterpreted inferentialism describes how we are living in the life-world phenomenologically .

References

Brandom. R., Making It Explicit, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1994.

Brandom, R., “Knowledge and the Social Articulation of the Space of Reasons”, Phenomenological Research, Vol. 55(4), 1995, 895-908.

Brandom. R., Articulating Reasons, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2000.

Brandom. R., “Responses,” Pragmatics and Cognition, Vol. 13(1), 2005, 227-249.

Davidson. D., “On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme,” Inquiries into Truth and Interpretation, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984, 183-198.

Hattiangadi. A., “Making It Implicit,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, Vol. 66(2), 2003, 419-431.

McDowell. J., “Reply to Gibson, Byrne, and Brandom”, Philosophical Issues, Vol. 7, 1996, 283-300.

McDowell. J., “Motivating Inferentialism,” The Engaged Intellect, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2009a, 288-307.

McDowell. J., “How Not to Read Philosophical Investigations,” The Engaged Intellect, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2009b, 96-111.

Sellars, W., “Empricism and the Philosophy of Mind,” Science, Perception and Reality , Atascadero, California: Humanities Press, 1991, 127-196.

Presentation Slides