Ⅲ. Criticisms of the “big bold claim”

Though Brandom argues that inferentialism can suggest systematic theories for describing a lot of semantic vocabulary, it is questionable whether inferentialism is the only or the best philosophical position for analyzing our linguistic practices. McDowell points out that it is a logical leap to conclude that inferentialism proved its superiority to other theories from the fact that inferentialism can explain some semantic vocabulary. Let us summarize the criticisms of inferentialism, in support of McDowell’s perspective, with three heads. Does inferentialism really has more explanatory power than representationalism? Does inferentialism really solve the dilemma of rule-following? Does inferentialism really give an account of direct contact with reality?

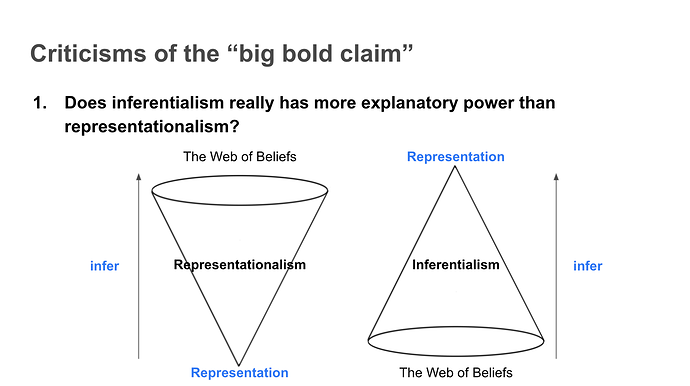

1. Does inferentialism really has more explanatory power than representationalism?

McDowell doubts whether inferentialism can really show that it has more explanatory power than its rival philosophical positions. Especially, he criticizes that though inferentialism inverses the order of semantic explanation that representationalism suggests, it does not fully show the reason to follow its new order. That is,

representationalism claims that elementary sentences in our language correspond to the world. It tries to construct the meaning of ordinary language from the designational relations between the elementary sentences and the states of affairs. However,

inferentialism claims that sentences of the world also postulate the game of giving and asking for reasons. It tries to analyze all representational semantic vocabulary (such as ‘true,’ ‘refer,’ ‘of,’ ‘about’ etc.) on the basis of its expressive role in implicit inferential relations.

Suppose a sentence “The cloth is red.” While representationalism explains that the sentence represents the colored and spatially extended cloth in the world, inferentialism explains that the sentence is inferred from our background knowledge (such as “I am placed in the normal epistemic condition,” “My eyes have reliable differential responsive dispositions of external objects.”, “There is no reason to challenge my perceptual ability” etc.). While the former considers the representation (“The cloth is red.”) to be a premise for further inferences, the latter considers it to be a conclusion of implicit inferences.

The two philosophical positions merely start with different theoretical presuppositions. The order of semantic explanation itself does not show which philosophical position is more plausible to explain the meaning of assertion. In order to criticize representationalism, inferentialism has to not only advertise its system but also vindicate the advantage of its system. However, it seems that inferentialism hastily concludes its superiority to representationalism from its explanatory power over some semantic vocabulary. McDowell points out that inferentialism has to prove its superiority:

Inferentialism is nothing if not a general thesis. That semantic insights can be achieved in this or that particular area by focusing on inferences does not vindicate inferentialism. It is compatible with the view that semantic concepts come in a package, each intelligible partly in terms of the others, rather than conforming to the foundational structure that inferentialism envisages. Brandom’s talk of the proof being in the pudding would be to the point if he had actually given a semantic account of a language in inferentialist terms. But what he has given is really only an advertisement for such a thing. The question whether his proffered motivation is convincing matters more than he acknowledges. (McDowell, 2009a: 307)

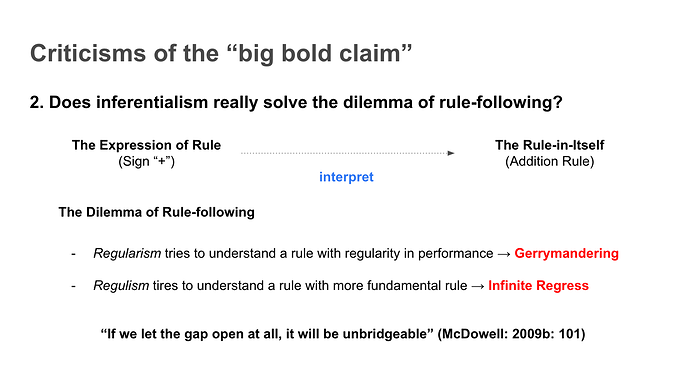

2. Does inferentialism really solve the dilemma of rule-following?

What is more problematic is that inferentialism even fails to suggest an answer to the problem that it assures to solve. For example, inferentialism emphasizes that it has more explanatory power than representationalism in that it has a strength in dealing with the dilemma of rule-following. It claims that how we can follow rules in our language cannot be explained by appealing to external facts outside our language. Let us think about the operation sign “+” in mathematics. The representationalist theories that try to explain how we can understand the sign “+” as the expression of the addition rule face a serious dilemma that cannot be solved:

If the theories try to explain the meaning of the sign by suggesting particular cases that correspond to the rule of addition, they will realize that there are infinite errors that can be gerrymandered as correct cases of addition.

If the theories try to explain the meaning of the sign by postulating the more fundamental rule than the sign “+,” they will realize that the attempt to explain the rule with the more fundamental rule falls into an infinite regress.

These are two “master arguments” that inferentialism uses to criticize representationalist theories while putting forward its own normative pragmatics that explicit rules are the expression of implicit normativity that we always follow. However, it seems that the “master arguments” can be applied not only to representationalist theories but also to inferentialist theories. As representationalism appeals to external facts to bridge the gap between the sign “+” and the addition rule, inferentialism also appeals to similar external elements outside of language:

If inferentialist theories claim that we always have “reliable differential responsive dispositions” that guarantee us to correct rule-following, they will be criticized that there are infinite incorrect dispositions that can be gerrymandered as correct applications of addition.

If inferentialist theories claim that we always know more fundamental normativity to determine which disposition is correct, they will be criticized that the attempt to introduce such normativity falls into an infinite regress.

Whichever they select as a solution to the dilemma, they cannot evade their “master arguments.” (see Hattiangadi, 2003) As long as rule-following is regarded as the problem of how to interpret the sign (expression of rule) as the rule-in-itself, neither representationalism nor inferentialism can solve the problem at all. McDowell points out that if we take the gap between the expression of rule and the rule-in-itself for granted, any attempt to bridge the gap cannot be successful:

We must not acquiesce in the idea that an expression of a rule, considered in itself, does not sort behaviour into performances that follow the rule and performances that do not. Once we start thinking like that, it can seem for a moment that an interpretation can bridge the gap—that adding an interpretation can yield something, the expression of the rule under an interpretation, that does effect the required normative sorting of behaviour. But only for a moment, until we realize that the same thought will be just as plausible about whatever we try to conceive as an expression of the interpretation. If we let the gap open at all, it will be unbridgeable. This way we lose our grip on the idea of an expression of a rule, or an expression of an interpretation. In the end we lose our grip on the idea of an expression of anything. (McDowell: 2009b: 100-101, my emphasis)

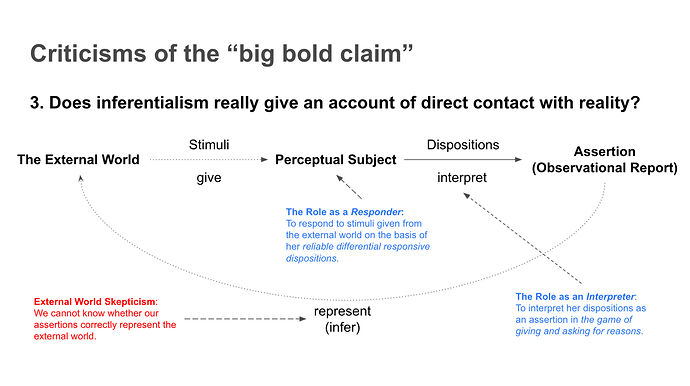

3. Does inferentialism really give an account of direct contact with reality?

The dilemma of rule-following is relevant to another serious problem, so-called external world skepticism. Though inferentialism gives an account of “rational constraint” from the external world on the basis of reliable differential responsive dispositions and the game of giving and asking for reasons, it is questionable whether the attempt to reduce direct contact with reality into inferential relations is possible. That is, inferentialism reduces rational constraint into observational reports that are formed by responding to external stimuli, with reliable differential responsive dispositions, in the game of giving and asking for reasons. In order to explain rational constraint, it distinguishes dual roles of a perceptual subject:

As a responder, the subject responds to external stimuli with her reliable differential responsive dispositions.

As an interpreter, the subject interprets her dispositions as an assertion (such as “This is a red cloth.”) in the game of giving and asking for reasons.

Therefore, the perceptual subject postulated by inferentialism is a person who always infers the external world from some assertions. The assertions interpreted from these dispositions are regarded as observational reports, which are resulted from rational constraints and can be used as foundations for further inferences of the external world.

However, the attempt to infer the external world from observational reports falls into external world skepticism. As the dilemma of rule-following takes a gap between the expression of rule and the rule-in-itself for granted and tries to bridge it with interpretations of the rule, external world skepticism also takes a gap between observational reports and the external world for granted and tries to bridge it with inferences from interpreted dispositions. Therefore, all the assertions (representations) of the external world in inferentialism are regarded as a kind of hypothesis that should be examined and can be refuted. There is no direct contact (or touch) with reality but the indirect inference of the external world. McDowell criticizes that inferentialism cannot give an account for direct contact with reality:

It would not help with the problem I am posing for Brandom to note that the two personae, those of responder and interpreter of responses, can coincide in a single individual. The assumption that we can credit the people Brandom wants to see as interpreters with observational capabilities was only provisional. The difficulty arises again about how Brandom can be entitled to the idea that an interpreter is in touch with the relevant aspects of reality. It can only be qua responder—qua capable, herself, of responses that are intelligible as reports—that a person who is supposed to be an interpreter comes into our view as able to observe the relevant aspects of reality. [……] And here as before, Brandom’s picture leaves the fact itself, as the external rational constraint that it is on the activity of deciding what to believe, out of her view qua responder. That means that the supposed interpreter’s observational hold on reality is in turn made unintelligible by the picture’s externalism. (McDowell, 1996: 295)

(To be continued in the next presentation)