“The big, bold claim that ties together the two halves of MIE is that when the commitments and entitlements that have been argued to be a necessary feature of practices recognizable as involving giving and asking for reasons (and hence, assertions, which are what can both be given as reasons and have reasons demanded for them) are elaborated in this practical-consequential structure, the result is sufficient for genuinely discursive (that is, conceptual) practice: that the performances should count as assertions and the moves as inferences. This is the claim that McDowell rejects.” (Brandom, 2005: 238)

Ⅰ. Introduction

Robert Brandom summarizes his model of linguistic practice, the game of giving and asking for reasons, with the term “big bold claim.” This term appears in his response to John McDowell. Against the criticism that inferentialism cannot justify its theoretical presuppositions, Brandom tries to prove the explanatory power of inferentialism by emphasizing that it can describe a lot of semantic vocabulary from minimum raw materials. In this presentation, I will outline Brandom’s model of linguistic practice on the basis of his “big bold claim” (Ⅱ), criticize some of its theoretical presuppositions in support of McDowell’s perspective (Ⅲ), and suggest a way to justify the significance of inferentialism despite the limitations within its theoretical presuppositions (Ⅳ).

Ⅱ. What is the “big bold claim”?

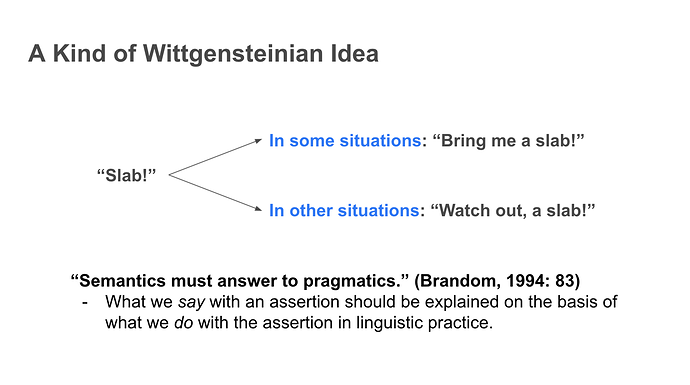

Brandom starts his project to establish inferentialism with the slogan that “semantics must answer to pragmatics.” (Brandom, 1994: 83) He follows a kind of Wittgensteinian idea that what we say with an assertion should be explained on the basis of what we do with the assertion in linguistic practice. As Wittgenstein’s well-known example points out, the meaning of the call “Slab!” is understood in different contexts in different ways. The same call “Slab!” can be used as an order “Bring me a slab!” in some situations and as a caution “Watch out, a slab!” in other situations. The way it is used in language-games determines the way it is understood to us. This is why Brandom emphasizes the priority of pragmatics over semantics. He believes that by constructing the model of linguistic practice, semantics can have its own ground to solve the problems in the philosophy of language (though Wittgenstein himself refused to make the general theory of language-game).

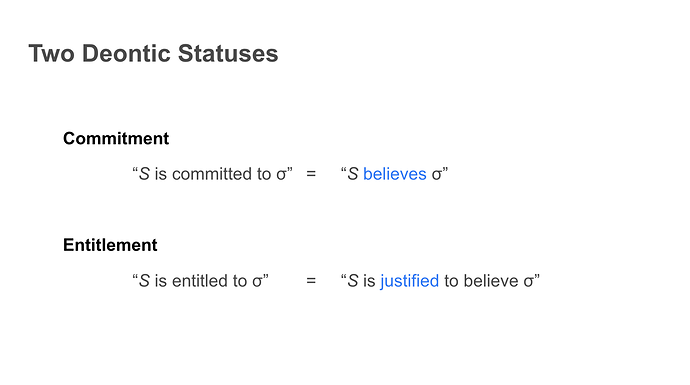

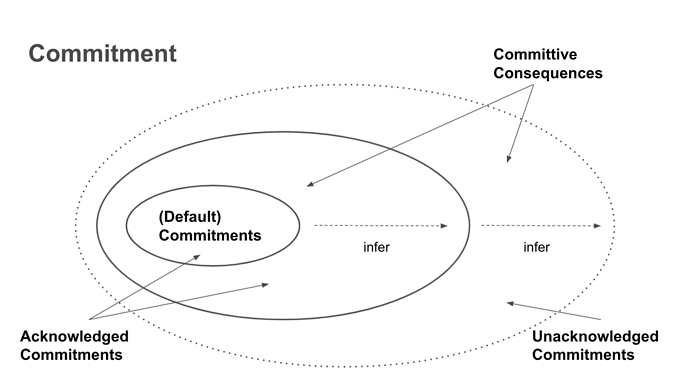

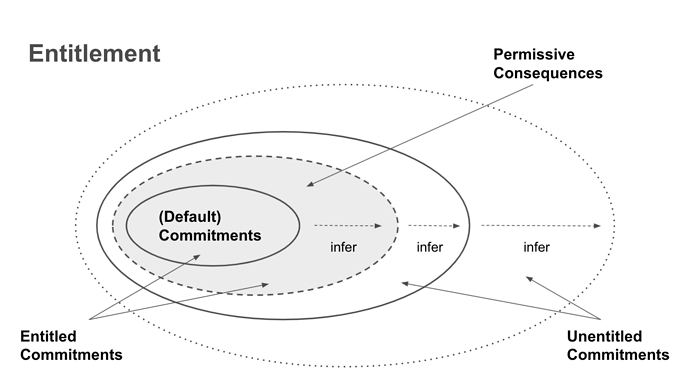

Inferentialism systemizes the model of linguistic practice from two kinds of basic elements, so-called commitments and entitlements. These are deontic statuses that assertions in linguistic practice express and vindicate.

(1) To be committed to an assertion is to believe the assertion. In asserting what she believes, a participant in linguistic practice places herself in a wide range of inferential relations. If she is committed to an assertion, she ought to be committed to other assertions that are inferentially related to the former assertion. For example, one who asserts “The swatch is red” ought to assert “The swatch is colored.” In these kinds of cases, the latter commitments that are inferred from the former ones are called ‘committive consequence.’

(2) To be entitled to an assertion is to be justified to believe the assertion. In committing herself to assertions, a participant in linguistic practice is asked by her interlocutors to distinguish assertions that are justified (have reasons) to believe and assertions that are not. If she is entitled to a commitment, she is allowed to make an assertion that expresses the commitment. As some commitments are inferred from other commitments, entitlements also are inherited from one assertion to other assertions in inferential relations. In these kinds of cases, the latter entitlements that are inherited from the former ones are called ‘permissive consequences.’

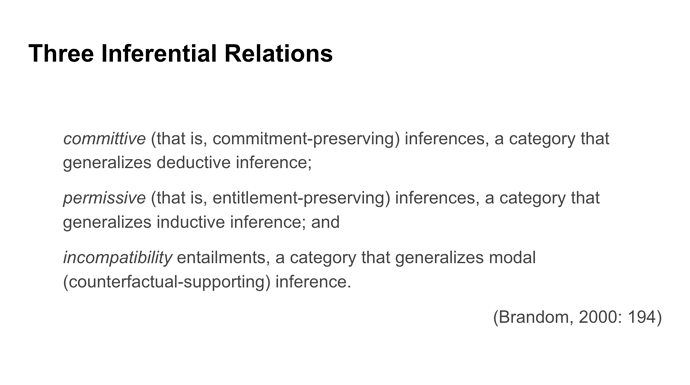

From these two deontic statuses, Brandom induces three kinds of inferential relations that consist of linguistic practices: committive inferences, permissive inferences, and incompatibility entailments. He distinguishes them as follows:

committive (that is, commitment-preserving) inferences, a category that generalizes deductive inference;

permissive (that is, entitlement-preserving) inferences, a category that generalizes inductive inference; and

incompatibility entailments, a category that generalizes modal (counterfactual-supporting) inference.(Brandom, 2000: 194)

The incompatibility entailments show that commitment and entitlement are interrelated to each other. Consider that one who asserts “The swatch is red” is not allowed to assert “The swatch is green.” It is one of the cases that incompatibility among commitments occurs. That is, commitments are incompatible when a commitment to an assertion excludes the entitlement to other assertions.

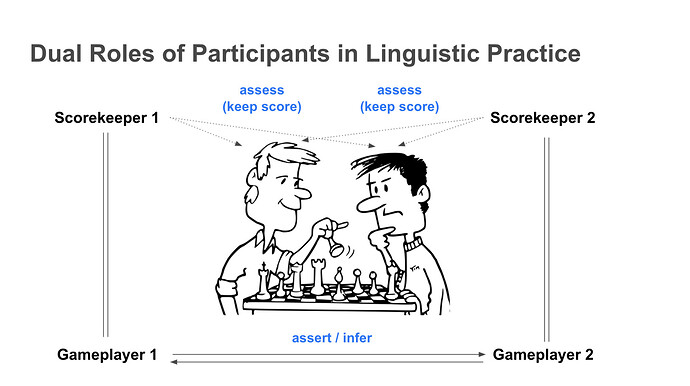

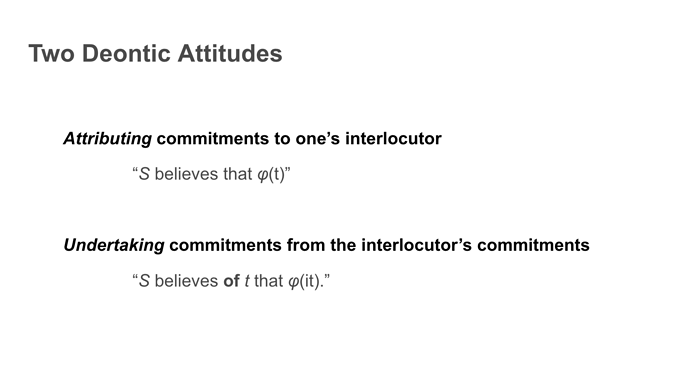

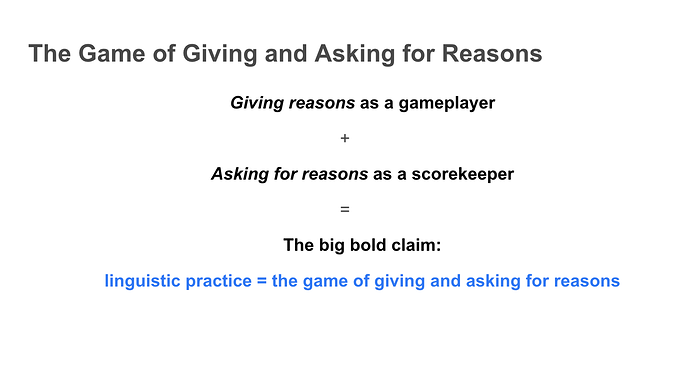

Inferentialism tries to describe the linguistic practice, in which participants assess their deontic statues, with the model of language-game, in which participants give and ask for reasons. In this language-game, the participants have dual roles at the same time: the roles of gameplayer and scorekeeper. Especially, the role of scorekeeper is closely related to the two kinds of deontic attitudes, so-called attributing and undertaking.

(1) As a gameplayer, a participant in linguistic practice ought to express commitments and vindicate entitlements to her assertions. It is often explained that asserting is a kind of performance and inference a kind of move in the language-game. That is, by committing and entitling to assertions, a participant does some significant acts in the game. Likewise, by acknowledging the committive and permissive consequences of her commitments and entitlements, a participant alters her status in the game. ‘Giving reasons’ is the term that sums up these processes of committing to assertions and entitling to them.

(2) As a scorekeeper, a participant in linguistic practice ought to reflect on situations that occur in the game. On the one hand, by attributing commitments to her interlocutors, she should grasp what kinds of and how many assertions belong to her interlocutors. However, on the other hand, by undertaking some commitments from her interlocuter’s commitments, she should distinguish the commitments that can be acknowledged by her from the commitments that cannot. The criterion of the undertaking is whether the interlocutor’s commitments are justified in the scorekeeper’s already-established commitments. ‘Asking for reasons’ is the term that sums up these processes of assessing commitments and entitlements of interlocutors.

Therefore, Brandom describes his model of linguistic practice as the game of giving and asking for reasons. That is, the participants of the game give reasons for her assertions, as gameplayers, and ask for reasons for her interlocutor’s assertions, as scorekeepers. In these processes, they do some significant acts and alter their statuses in each stage of the game. The scores that they get and lose while giving and asking for reasons determine the normative statuses in the game. The meaning of assertion (what an assertion refers to, how it can be interpreted, whether it is true, etc.) is understood in accordance with the scores. So-called Brandom’s “big bold claim” is that this model of linguistic practice is necessary and sufficient conditions for the meaning of assertion.

(To be continued in the next presentation)